Research by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin, the Santa Fe Institute, and Fractal Therapeutics suggests infection rates in the surrounding community are not a reliable measure for estimating the level of risk for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission in schools.

Claims of in-person schooling being safe and not increasing infection have been based on testing students who present with symptomatic infection rather than proactive testing of potentially asymptomatic students. However, previous studies have shown that most COVID-19 cases are spread through asymptomatic spread, and children are more likely to have asymptomatic infection than adults.

The findings throw into question whether schools should remain closed to mitigate the risk for COVID-19 infection. The authors write:

“We found that the ratio of cases occurring in and out of schools and low numbers of documented in-school transmission events are not sufficient to distinguish these two scenarios. While there are compelling arguments for returning to in-person learning, particularly as SARS-CoV-2 vaccine coverage increases, a robust understanding of the limitations of the metrics being used to assess SARS-CoV-2 transmission is critical for risk management.”

The study “Detecting in-school transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from case ratios and documented clusters” is available as a preprint on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

How they did it

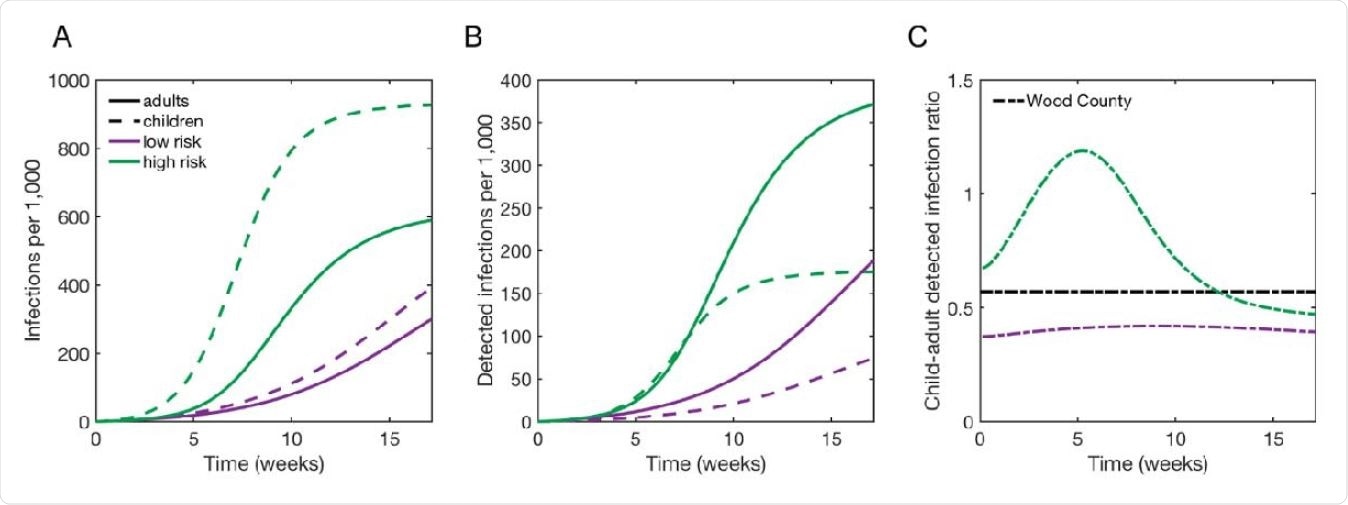

The researchers modeled two scenarios — one low-risk and one high-risk — of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to evaluate the ratio of infection rates in children, which included a lack of detected in-school outbreaks.

The model assumed children would show a 21% lower chance of presenting with COVID-19 symptoms compared to 70% of adults. It also assumed all symptomatic infections would be identified.

The high-risk scenario predicted high SARS-CoV-2 transmission among school children and adults in the community.

The simulations suggest that even when schools increased SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the community, the number of detected cases in children was lower than adults — even when the actual incidence was much higher.

The team also wanted to confirm that documented in-school transmission was insufficient in detecting asymptomatic cases. They looked at the probability of detecting outbreaks in schools using the symptom-gated forward contact tracing — a common approach to evaluating cases in schools relying on the appearance and reporting of two consecutive symptomatic cases.

Given a 21% detection rate for symptomatic infection, the researchers estimated approximately 4.4% of total COVID-19 cases from child-to-child transmission would be detected.

They predicted about 28% of initial cases would infect at least one child, and approximately 11.5-22% of these cases would infect a child who later develops noticeable symptoms.

“Given the difficulty of ascertaining child-to-child SARS-CoV-2 infections via symptom-gated forward contact tracing, low numbers of documented events do not necessarily indicate a lack of in-school transmission.”

The findings indicate that the absence of symptomatic evidence of in-school transmission is not a sign SARS-CoV-2 is absent from schools.

Final thoughts

The results affect schools that only test for symptomatic infections. Hence, the results of this study would not apply to schools with asymptomatic COVID-19 surveillance.

Results of community transmission not reflective of the school environment are limited by students with hybrid or distance learning. The researchers note the model does not assume any predictions for adults working in schools or children, not at school. These two groups would be more likely to be affected by their surrounding community.

However, they found that as children and adults come more into contact, the total infection rates increased.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Johnson, KE. Detecting in-school transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from case ratios and documented clusters. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.26.21256136, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.26.21256136v1

Posted in: Child Health News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Children, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Reproduction, Research, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, students, Syndrome, Therapeutics, Vaccine

Written by

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira graduated with a Bachelor's in Integrative Neuroscience, where she then pursued graduate research looking at the long-term effects of adolescent binge drinking on the brain's neurochemistry in adulthood.

Source: Read Full Article