While estimates vary widely, the data suggests that Covid may leave a legacy of consequences after the pandemic is over

Tasha Clark tested positive for Covid-19 on April 8, 2020. The Connecticut woman, now 41, was relieved that her symptoms at the time — diarrhea, sore throat and body aches — didn’t seem particularly severe. She never got a fever and wasn’t hospitalized. So she figured that if the virus didn’t kill her, within weeks she’d go back to her job and caring for her two children.

She significantly miscalculated. More than a year later, she’s a textbook example of a Covid long-hauler.

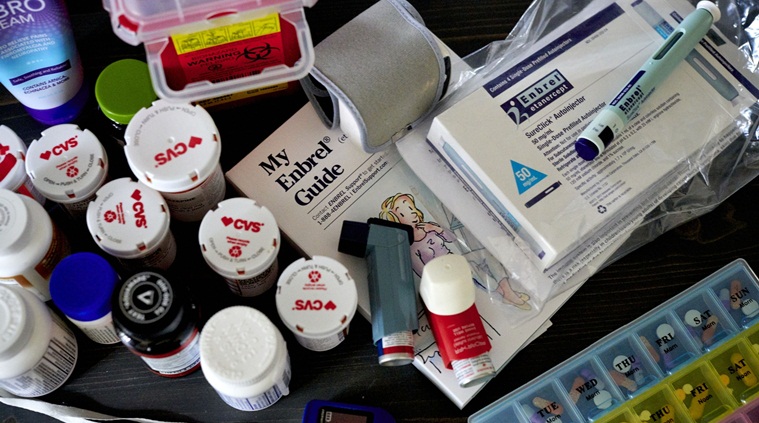

Clark suffers from an array of disabling symptoms including blowtorch-like nerve pain and loss of sensation in her arms and legs, spine inflammation that makes it difficult to sit up straight, brain fog, dizziness and a soaring heart rate when she stands. She takes steroids and nine other prescription medicines, including twice-monthly infusions of immune therapy at a Yale University clinic to treat the neurological complications.

When her front-desk job at a physical rehabilitation center couldn’t accommodate her disability, Clark had to take a lower-paying medical billing position. Her life outside of work is a never-ending odyssey of medical appointments, scans and lab tests. “I never in a million years thought that a year later my life would be reduced to what it has been,” says Clark, who lives with her husband and two school-aged girls in Milford. “Not knowing if I will ever recover is scary.”

The scope of the mysterious lingering symptoms triggered by Covid-19 is emerging more clearly, based on cases like Clark’s. But more than a year into the pandemic, what’s causing the symptoms and how best to treat them is anything but clear. Making research especially difficult is that there is such a wide range of health issues involved — from brain fog to cardiovascular problems to rare cases of psychosis — and there’s no agreed-upon metric for who qualifies as a long-haul patient.

“There is no consensus on how to define, diagnose or measure this syndrome,” Steven Deeks, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, told the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s health panel on April 28. “Everyone is using different definitions and the state of the art is a mess.”

While estimates vary widely, the data suggests that Covid may leave a legacy of consequences after the pandemic is over. A British government survey found that almost 14% of people with Covid reported symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks. In another study from the University of Washington, one-third of those diagnosed with mild Covid cases still had symptoms about six months later.

Further, non-hospitalized Covid-19 patients treated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs had a 59% increased risk of dying in the six months after contracting the disease compared to those who didn’t get it, and suffered from conditions such as blood clots, diabetes, stroke and nervous system problems, according to findings published in April in the journal Nature.

“We don’t understand what is happening with their biology,” says Serena Spudich, a Yale University neurologist treating post-Covid patients. “It is really, really unknown at this point.” While the patients’ symptoms are clear, brain MRI scans and other tests are often unrevealing, making it tough to determine the cause of the symptoms, she said.

To get a better grip on the problem, the National Institutes of Health is spending $1.15 billion to research long-term Covid and will focus on assembling a giant cohort of tens of thousands of post-Covid patients, who will share data from mobile apps and wearable devices. It has already received 273 research proposals and will announce funding in weeks, NIH director Francis Collins told Congress.

Answers can’t come too soon for Eddie Palacios, a 50-year-old commercial real estate broker in Naperville, Illinois. A month after getting a mild case of Covid last September he began forgetting words. One day, he couldn’t remember where he was after climbing onto the roof to clean the gutters; his son had to help him down.

“There is definitely memory loss, and headaches that won’t go away,” says Palacios, who is in cognitive rehab at Northwestern Medicine and takes the prescription stimulant modafinil, used to treat narcolepsy, to boost his alertness.

Still, he must take extensive notes during conversations with clients, something he never used to do. He says he’s fortunate that he can do his job from home. “If I were a 9-to-5 guy, I’d be unemployed,” he says.

Autoimmune Reaction

What makes people long-haulers? There are at least three possibilities. One leading theory is that the battle with the virus sets off an autoimmune reaction that persists long after the actual virus. This may be what has happened to Clark. The theory is that “the immune system is cranked up” during the initial illness but once the virus is gone, it doesn’t come back down, says Avindra Nath, a researcher at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Another possibility is that fighting Covid-19 leaves behind a detritus of viral particles that sets up a generalized cycle of inflammation long after the pathogen itself has departed. This may help explain why some people continue to test positive long after their infections appear to have cleared.

A third theory is that the virus may find hiding places in human tissues, allowing it to emerge weeks or months later when immunity weakens. Other viruses such as HIV and herpes simplex are known to hide out inside the body for years. If there is such a viral reservoir “it’s probably very difficult to get at, it could be very deep in some tissues,” said Akiko Iwasaki, a Yale University immunologist.

The hidden reservoir concept, while unproven, is consistent with the fact that some long-haulers initially have milder symptoms, and could also explain anecdotal reports that vaccines provide relief for long-haul patients.

While researchers hunt for answers, major medical centers such as Northwestern Medicine in Illinois and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York have opened clinics to manage patients’ myriad symptoms, providing help to those lucky enough to get it. Yale’s neurocovid clinic was set up this past October and has treated about 100 patients, including Clark.

Clark’s husband, Richard Zayas, a 47-year-old carpenter, came down with Covid in early April 2020. A few days later, she developed a horrible taste in her mouth, unlikely anything she had ever experienced before.

The first neurological symptoms came a week into her illness, when she burnt her arm taking something out of the oven because she didn’t notice the hot pan touching her. A few weeks later, just as her sore throat and cough were subsiding, she began losing sensation in her legs. Coming home from a drive, her legs gave out and she had to pull herself up the steps to her house by her arms. Though she suspected it was a complication of Covid, doctors at the local emergency room said a lot of things could be causing the symptoms and sent her home without extensive tests, she says.

Burning Pain

A skin biopsy later found signs of nerve damage, and doctors put her on gabapentin for the pain. But her symptoms worsened, and by July she was diagnosed with peripheral polyneuropathy. Over the summer, she fell multiple times going up and down the stairs in her house, or walking in the yard. This winter, burning pain in her feet was so bad that several times she went outside and stood barefoot in the snow or on bare concrete to numb the pain.

“My skin feels like someone is holding a blowtorch to it,” she says.

Since getting sick, Clark says she has had more than 50 doctor visits, and numerous procedures including two lumbar punctures, MRI scans of the pelvis, cognitive tests and multiple sleep studies. In addition to neuropathy, she’s been been diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, an autoimmune-related arthritis of the spine, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which produced rapid heartbeat and a light-headed feeling upon standing.

Doctors “think my immune system went in overdrive when I got the virus and since never shut off,” she said. “It has basically been attacking my body ever since.”

When other treatments didn’t fully improve her symptoms, Yale doctors early this year put Clark on infusions of intravenous immune globulin, a costly antibody infusion. Lindsay McAlpine, a neurology resident at Yale’s neurocovid clinic, says they only give immunoglobulin to post-Covid patients whose symptoms have a clear autoimmune link.

After being away from her front-desk job for eight months, Clark went back remotely in December but said she had to quit when her bosses insisted she return to the office. She found a medical billing job that can be done from her armchair. But it pays $1.47 an hour less, meaning she has to work overtime to keep up. She is so exhausted after work she can’t do much at home.The scariest part for Clark is not knowing how long the symptoms will last. When she contracted Covid more than 13 months ago, “I thought maybe two or three weeks tops and I would be back to my old self,” she says. “I have been sick every day since.”

Source: Read Full Article