People who had received a first dose of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and received an mRNA vaccine for their second dose had a lower risk of infection compared to people who had received both doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. This is shown in a nationwide study performed by researchers at Umeå University, Sweden.

“Having received any of the approved vaccines is better compared to no vaccine, and two doses are better than one,” says Peter Nordström, professor of geriatric medicine at Umeå University. “However, our study shows a greater risk reduction for people who received an mRNA vaccine after having received a first dose of a vector-based, as compared to people having received the vector-based vaccine for both doses.”

Since the use of Oxford-AstraZeneca’s vector-based vaccine against COVID-19 was halted for people younger than 65 years of age, all individuals who had already received their first dose of this vaccine were recommended an mRNA vaccine as their second dose.

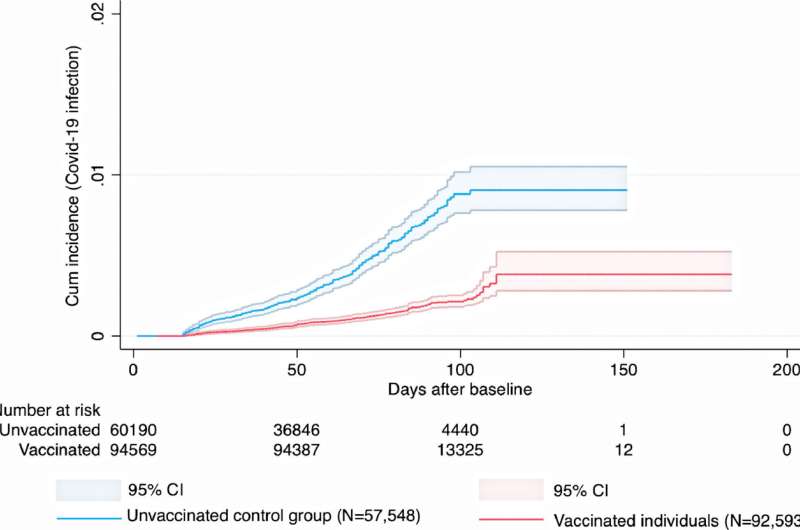

During a 2.5-month average follow-up period after the second dose, the study showed a 67% lower risk of infection for the combination of Oxford-AstraZeneca + Pfizer-BioNTech, and a 79% lower risk for Oxford/AstraZeneca + Moderna, both compared to unvaccinated individuals. For people having received two doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, the risk reduction was 50%. These risk estimates were observed after accounting for differences regarding date of vaccination, age of the participants, socioeconomic status, and other risk factors for COVID-19. Importantly, the estimates of effectiveness apply to infection with the Delta variant, which was dominating the confirmed cases during the follow-up period. There was a very low incidence of adverse thromboembolic events for all vaccine schedules. The number of COVID-19 cases severe enough to result in inpatient hospitalization was too low for the researchers to be able to calculate the effectiveness against this outcome.

Previous research has demonstrated that mix-and-match vaccine schedules generate a robust immune response. However, it has been unclear to which extent these schedules may reduce the risk of clinical infection. This is the knowledge gap that the new study conducted by the Umeå researchers aimed to fill. The study is based on nationwide registry data from the Public Health Agency of Sweden, the National Board of Health and Welfare, and Statistics Sweden. In the main analysis, about 700,000 individuals were included.

Source: Read Full Article