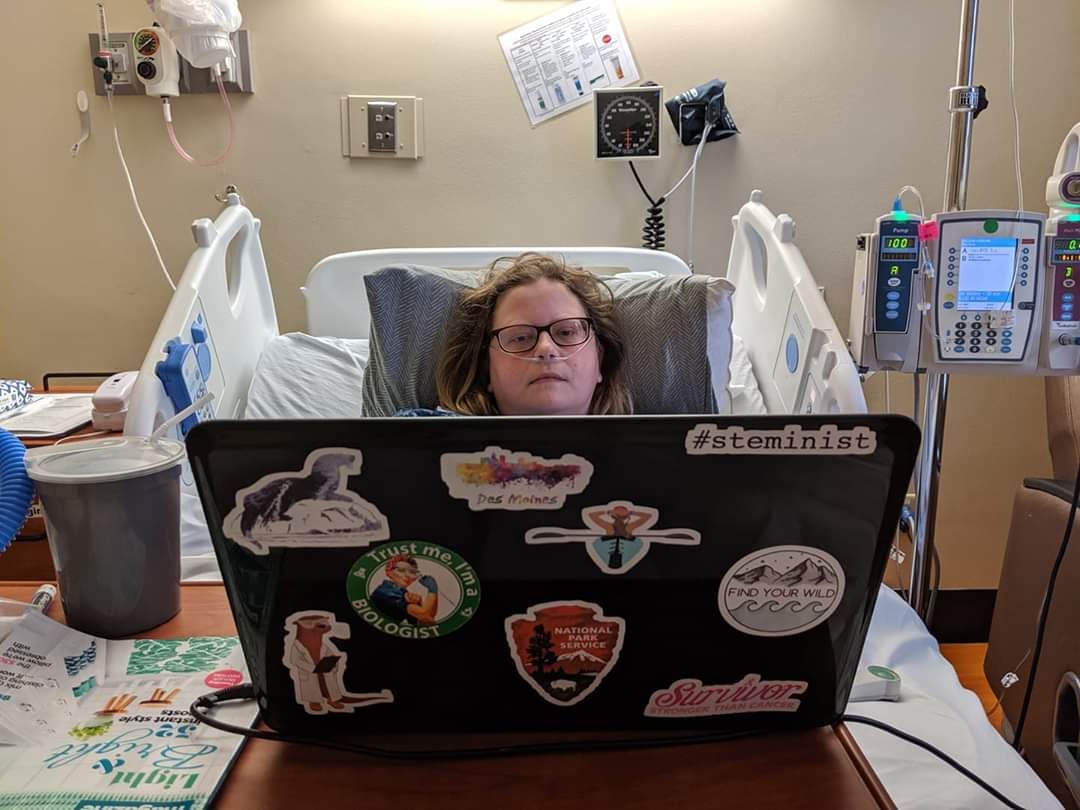

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

The surgery was scheduled for March 20. I had already had pretty in-depth discussions with nurses from the surgery and anesthesia departments about all of the preoperative details. But on March 18, I got a call from the physician’s assistant who works with my surgeon, and I knew what she was going to say as soon as I heard her voice: Surgery on my reconstructed breast had been canceled due to COVID-19.

Five years ago, just before my 30th birthday, I was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer.

Since then, I’ve had a unilateral mastectomy, five months of chemotherapy, 28 radiation treatments, and four years of hormone blockers. I’ve had no evidence of disease since my mastectomy on June 19, 2015.

I’ve also had three different types of breast reconstruction. First, in March 2016, I had reconstruction with a breast implant and a breast reduction on my left breast to match its size. But the implant never really settled well. It was very high—it didn’t look very natural next to my other breast. And it was very tight—the muscles in my chest felt like they were seizing up or cramping a lot, and it was even uncomfortable to lay on my stomach to go to sleep.

So then, in May 2019, I had something called DIEP flap reconstruction, which is when they basically take your belly, disconnect it from its blood supply, and reconnect it to the chest as new breast tissue. (During that surgery, we learned that the implant had actually ruptured a little bit.)

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Almost all DIEP flap surgeries are successful, but mine wasn’t. About two weeks after the surgery, I met with my surgeon, and as soon as he saw the tissue, his face fell. The tissue was dead. So a week or two after that, I had to basically have another mastectomy to get the new tissue removed.

Finally, I had what’s known as TUG flap reconstruction in November 2019. It involved a third surgeon and using the inner portion of my left thigh. It worked! The only issue is that the breast is really small because it’s from my inner thigh, so it’s basically like an A cup, compared to my native breast, which is now like a D. (Before, I had double Ds. I had a great rack, I’m not gonna lie.)

So I’m pretty lopsided now. I’m expecting to still have one or two more fat transfers, probably from my stomach, to my reconstructed breast, and then probably another reduction on my native breast so that they can match in size.

One of those fat transfers was supposed to take place in March.

Since my TUG flap, my surgeon took a job out of the country, but we had this little window where he was going to be back to do some surgeries and I was going to be on spring break from both my teaching job and being a PhD student.

At the time, the pandemic was starting to ramp up in Iowa, where I live. The university I teach for had just closed for the rest of the semester. In fact, I was really debating internally with myself: Is it moral for me to get the surgery at this point and take up protective personal equipment (PPE) and resources? Is it safe for the staff there? Is it safe for me? So I was a little relieved when they made the call for me.

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

After that, I didn’t hear from the hospital until mid-May (of course, they’ve had bigger issues to deal with), when the physician’s assistant called to tell me that my next surgery will take place on June 5.

She assured me that the hospital has enough PPE and is well prepared. My husband will have to drop me off and pick me up without entering the hospital, and the thought of waiting for surgery alone is daunting, to say the least. I’ll also have to drive two hours one-way to Iowa City for a COVID-19 throat swab test the day before my surgery because the test has to be done within the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics system. It’s inconvenient, but I’m happy to do it and keep my medical team safe.

I completely understood the hospital’s decision to delay, and I think it was the correct one given the pandemic.

But I’m feeling a little disappointed in a selfish way that I have had to wait longer to have my breast reconstructed. I’m just really ready to have my body put back together. One of the worst parts of this surgery being delayed is that we’re not just holding on one surgery; there’s going to be a series of surgeries and recoveries that follow. So it’s frustrating to not know what the timeline is going to look like and to not have an idea of what my body is going to look or feel like months or even a year from now.

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

I have to be on hormone blockers for five years before I can pause them to try to have kids because I had estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and progesterone receptor (PR)-positive breast cancer, which means the cancer cells grow in response to estrogen and progesterone. So when I finish those up in 2021 and my husband and I are 35, I want to get the ball rolling with IVF as soon as I can.

The goal was to have the reconstructions complete by this summer. Then I could have until the end of next year to just exist in my body without having it be something that needs to be fixed or manipulated or changed, have a short amount of time to travel, to swim, to work out normally—because rumor has it pregnancy is kind of hard.

The delay to my surgery is messing with the timeline I had in mind for starting a family.

While the fat transfers are a quicker recovery, the reduction on my native breast is a longer ordeal, and I’m trying not to miss any more of my job or sacrifice working on my PhD. I don’t think it will be possible to squeeze in multiple fat transfers and a reduction on my native breast in the next few months, which means the next big chunks of time I have aren’t until this coming winter break and next summer, or maybe spring break next year. As a result, I’ll probably have to either push back IVF or go straight from the surgery into trying to be pregnant.

Plus, experts are predicting a second wave of outbreaks, so really any concept of a timeframe I had is out the window. I think I’m just going to have to undergo my future procedures based on the surgeon’s availability, breaks in the school year, and the waves of this pandemic.

Before cancer, you’ve got all the options in the world open to you, and then cancer goes, “Nope, you’ve got a limited set of choices.” And to have that reduced even further—on one hand, I’m used to it; on the other hand, it’s getting really old. I’m just tired of having cancer and these surgeries dictate the pattern of my life.

In those first few days after your diagnosis, you’re thinking, “Who cares what my breasts look like? I just want to live.”

But then you get through that terror of treatment, and you start to see the light at the end of the tunnel. You go, “Oh, wait, my appearance does matter to me. I’m still a young woman, and I still want to be able to wear a sports bra that supports me. I want to be able to buy a wedding dress that I look nice in.”

As you start to get back to your normal life, you start to remember those priorities. Reconstruction seems like it’s just a cosmetic thing, like it’s not a big deal. But it changes your mental health, it changes your outlook, and it changes in the way your muscles move and the balance of weight across your chest.

Even well-meaning people will say something like, “But you get a ‘free’ boob job.”

I joke a lot about cancer—that’s how I cope—and so I get why people say that. And yes, technically, the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1998 says insurance must also cover expenses related to the reconstruction of a breast after a mastectomy. But I would much rather not have gone through cancer than get a free boob job. It’s not an equal tradeoff—and I have paid so, so dearly, both literally and figuratively, in many other ways.

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Courtesy of Bridie Nixon

Reconstruction is a way of feeling normal again and not having this reminder every time I take a shower, every time I dress, every time I buy new clothes, of what I’ve been through—and all the work that still has to be done.

Reconstruction is a way of trying to put the trauma of the past five years behind me. And then, even if I’m not perfectly happy with my body, I could say, “Okay, this is it. I know what I’ve got to work with,” and I could start to embrace it. I could move forward. Right now, it’s more like being stuck in limbo.

Source: Read Full Article