It’s not often that a failed clinical trial leads to a scientific breakthrough.

When patients in the UK started showing adverse side effects during a cancer immunotherapy trial, researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Center for Cancer Immunotherapy and University of Liverpool went back through the data and worked with patient samples to see what went wrong.

Their findings, published recently in Nature, provide critical clues to why many immunotherapies trigger dangerous side effects—and point to a better strategy for treating patients with solid tumors.

“This work shows the importance of learning from early stage clinical trials,” says La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D., who co-led the new research with Christian H. Ottensmeier, M.D., Ph.D., FRCP, a professor with the University of Liverpool, The Clatterbridge Cancer Center NHS Foundation Trust, and adjunct professor at LJI.

Limited success with immunotherapies

Both Vijayanand and Ottensmeier are physician scientists, and Ottensmeier is an attending oncologist who treats solid tumor patients. In just the last decade, he has seen more and more patients thrive thanks to advances in immunotherapies, which work with the immune system to kill cancers.

“In the oncology world, immunotherapy has revolutionized the way we think about treatment,” says Ottensmeier. “We can give immunotherapies to patients even with metastatic and spreading disease, and then just three years later wave goodbye and tell them their cancer is cured. This is an astounding change.”

Unfortunately, only around 20 to 30 percent of solid cancer patients given immunotherapies go into long-term remission. Some people see no change after immunotherapy, but others develop serious problems in their lungs, bowel, and even skin during treatment. These side effects can be debilitating, even fatal, and these patients are forced to stop receiving the immunotherapy.

Important lessons from a clinical trial

The researchers at LJI and the University of Liverpool worked with samples from a recent clinical trial in the UK for patients with head and neck cancers. The patients were given an oral cancer immunotherapy called a PI3Kδ inhibitor. At the time, PI3Kδ inhibitors had proven effective for B cell lymphomas but had not yet been tested in solid tumors.

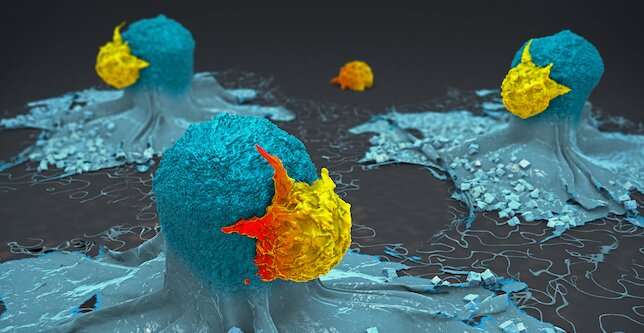

PI3Kδ inhibitors are new to the cancer immunotherapy scene, but they hold promise for their ability to inhibit “regulatory” T cells (Tregs). Tregs normally try to stop other T cells, called effector T cells, from targeting the body’s own tissues. Oncologists inhibit Tregs inside tumors so effector T cells can let loose and generate cancer-killing CD8+ T cells.

“Having an oral tablet that can take off the brakes—the Tregs—can be a great asset for oncologists,” says Vijayanand.

Unfortunately, 12 of the 21 patients in the trial had to discontinue treatment early because they developed inflammation in the colon, a condition called colitis. “We thought this drug wouldn’t be toxic, so why was this happening?” says Vijayanand.

LJI Instructor Simon Eschweiler, Ph.D., spearheaded the effort to go back and see exactly how PI3Kδ inhibitor treatment affected immune cells in these patients. Using single-cell genomic sequencing, he showed that in the process of increasing tumor-fighting T cells in tumors, the PI3Kδ inhibitor, also blocked a specific Treg cell subset from protecting the colon. Without Tregs on the job, pathogenic T cells, called Th17 and Tc17 cells, moved in and caused inflammation and colitis.

It was clear that the cancer trial patients had been given a larger PI3Kδ inhibitor dose than they needed, and the immunotherapy had thrown the delicate composition of immune cells in the gut out of balance.

The pathway that leads to the toxicity seen in the new study may be broadly applicable to other organs harboring similar Treg cells, and to other Treg cell-targeting immunotherapies like anti-CTLA-4, Eschweiler says.

New dosing strategy may save lives

The team found that intermittent dosing could be a valid treatment strategy that combines sustained anti-tumor immunity with reduced toxicity.

The researchers are now designing a human clinical trial to test the intermittent dosing strategy in humans.

“This research illustrates how you can go from a clinical study to a mouse study to see what’s behind toxicity in these patients,” says LJI Professor and Chief Scientific Officer Mitchell Kronenberg, Ph.D., whose lab led much of the mouse model work for the new study.

How to explain lack of toxicity in trials for B cell lymphomas? Eschweiler says lymphoma patients in previous studies had been given several prior therapies leading to an overall immunocompromised state. This means the lymphoma patients didn’t have the same type—or the same magnitude—of immune response upon PI3Kδ inhibition. Meanwhile, the head and neck cancer patients were treatment-naive. Their immune system wasn’t compromised, so the immune-related adverse events were both more rapid and more pronounced.

Overall, the new study shows the importance of studying not just personalized therapies but personalized therapy doses and schedules.

As Ottensmeier explains, doctors ten years ago only had one type of immunotherapy to offer. It either helped a patient or it didn’t. Doctors today have a rapidly growing library of immunotherapies to choose from.

Vijayanand and Ottensmeier are among the first researchers to use single-cell genomic sequencing tools to determine which therapeutic combinations are most effective in individual patients—and the best timeline for giving these therapies. In a 2021 Nature Immunology study, the pair showed the potential importance of giving immunotherapies in a specific sequence.

“If you design your clinical trials well and apply sophisticated genomics, you have a lot to learn,” says Vijayanand. “You can figure out what’s happening and go back to the patients.”

Their mission would not be possible without a highly skilled, international team of collaborators. “This study has been an extraordinary collaborative effort,” says Ottensmeier. “It’s taken groups of medical oncologists, surgeons, research nurses, our patients, and scientists—all working together on two sides of the pond.”

Source: Read Full Article