The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been caused by the rapid outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, which is capable of infecting many wildlife species. Animals living close to human beings are particularly vulnerable to being infected. If undetected, the animals could develop into reservoirs for the pathogen and, therefore, make it more difficult to contain the pandemic.

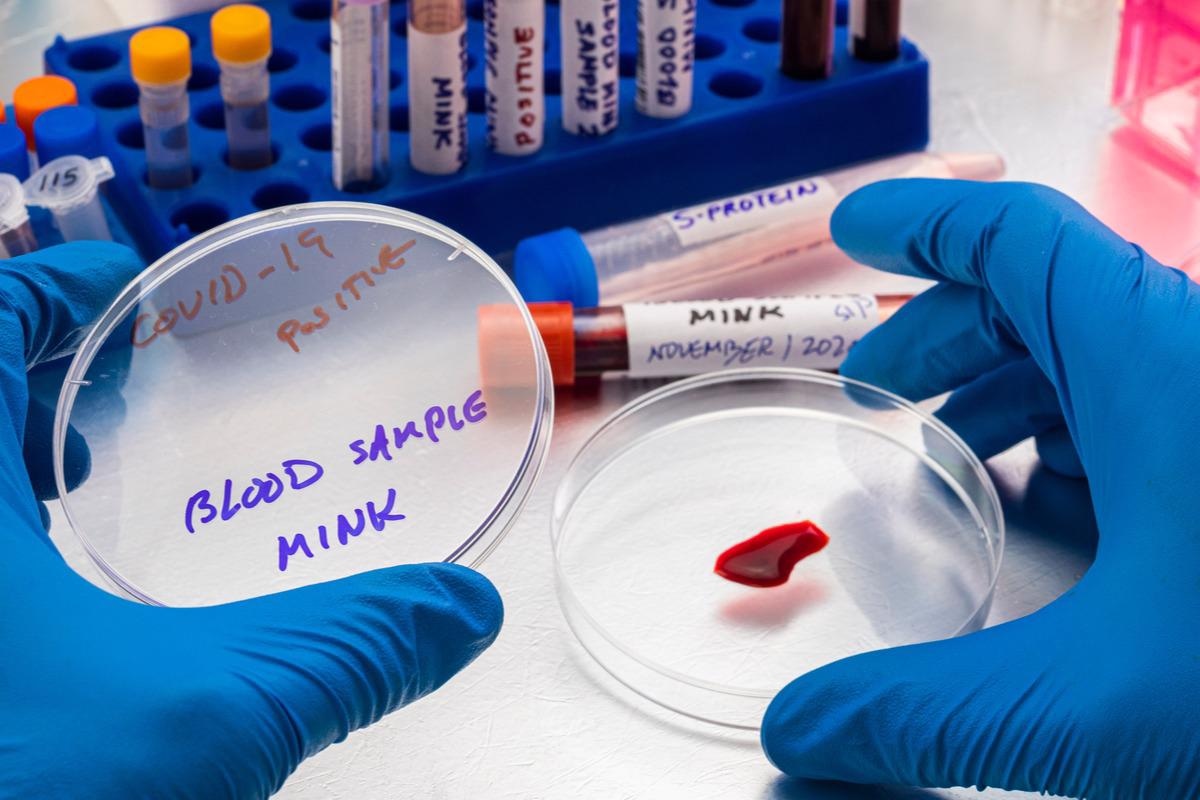

Study: SARS-CoV-2 wildlife surveillance in Ontario and Québec, Canada. Image Credit: felipe caparros/Shutterstock

Study: SARS-CoV-2 wildlife surveillance in Ontario and Québec, Canada. Image Credit: felipe caparros/Shutterstock

In a new study, published on the bioRxiv* preprint server, researchers conducted SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in urban wildlife from Ontario and Québec, Canada.

Background

Many domestic and wild animal species have been either naturally infected with SARS-CoV-2 or susceptible to the virus in experimental infections. Based on sequence analysis, some animals have also been identified as potential hosts. The SARS-CoV-2 infection has also been reported in wild or free-ranging animals, including American mink and white-tailed deer.

Spillover infections from humans or domestic animals into wildlife are concerning because of the harmful effects on wildlife and because these species could act as potential reservoirs for SARS-CoV-2, which in turn could lead to the emergence of more variants of concern (VoCs).

Researchers have stated that it is imperative to elucidate the epidemiology of the virus at the human-wildlife interface. This is important as it would aid in wildlife management and public health officials better plan management strategies. In the current study, scientists addressed this issue by conducting SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in wildlife across Ontario and Québec, Canada. These regions were chosen as they have high human population densities and include major urban centers such as Toronto and Montréal.

A new study

Scientists used a One Health approach and leveraged existing research, surveillance, and rehabilitation programs among multiple agencies to collect samples. Between June 2020 and May 2021, samples were collected from 776 animals from 17 different wildlife species. The samples were tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA. The presence of neutralizing antibodies was tested in a subset of 219 animals from 3 different species, namely, raccoons, striped skunks, and mink.

Key findings

No spillover of SARS-CoV-2 to wildlife in Ontario and Québec was detected. Raccoons and skunks were the most commonly tested species. A low quantity of infectious viruses from raccoons and skunks suggested they are unlikely reservoirs for SARS-CoV-2 in the absence of viral adaptations. Another study found that big brown bats are resistant to SARS-CoV-2 infection and do not shed the infected virus. Researchers also did not observe viral RNA in mink, but this could be due to the relatively small sample size.

One important point to be noted is that the aforementioned experimental studies were conducted using the parental SARS-CoV-2. Raccoons, skunks, and big brown bats may be susceptible to VoCs, and this issue needs to be investigated further. Also, challenge studies typically involve few young and healthy individuals, because of which they may not be representative of the complete range of infections in the wild.

Extensive research is being conducted to identify animals that could act as competent reservoirs for the virus. White-tailed deer are now considered a highly relevant species for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance. Continued surveillance efforts should be adaptive and include targeted testing of the relevant species as and when they are detected (mink, white-tailed deer, and deer mice in Ontario and Québec).

Limitations

The majority of testing was done by RT-PCR, which can only detect active infection. Antibody testing, which identifies resolved infection or exposure, could act as a suitable complement to the RT-PCR testing as that would make the study more robust. Second, the type of samples collected could have limited the ability to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is known that viral replication can vary among tissue types, as some are more optimal for viral RNA detection than others. The current study sampled animals based on pre-existing surveillance efforts, research, and rehabilitation programs. Scientists could not consistently collect the same samples from all animals, and these samples were not optimized.

Conclusion

Scientists claimed that one health approach is extremely important to understand and manage the risks of emerging zoonotic pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2. They leveraged existing research and surveillance to collect and test 1,690 individual wildlife samples. Viral RNA was not detected in the samples, but this does not exclude the possibility of spillover from humans to Canadian wildlife. Continued research in this area is required, particularly as novel VoCs continue to emerge. The research results will help inform public policy and protect the health of both Canadians and wildlife, now and in the future.

*Important notice

bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Greenhorn, E.J. et al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 wildlife surveillance in Ontario and Québec, Canada. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.02.470924 https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.02.470924v1

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Antibodies, Antibody, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Epidemiology, Pandemic, Pathogen, Public Health, Research, Respiratory, RNA, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Syndrome, Virus

Written by

Dr. Priyom Bose

Priyom holds a Ph.D. in Plant Biology and Biotechnology from the University of Madras, India. She is an active researcher and an experienced science writer. Priyom has also co-authored several original research articles that have been published in reputed peer-reviewed journals. She is also an avid reader and an amateur photographer.

Source: Read Full Article