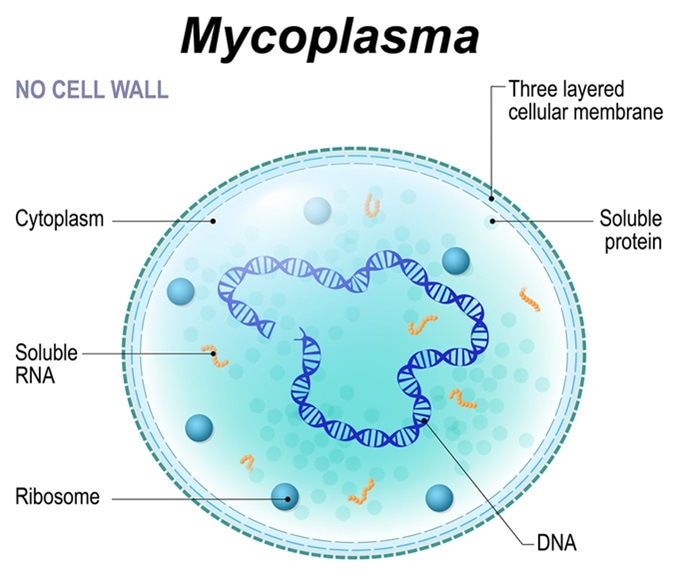

Mycoplasmas are considered to be the smallest free-living organisms known, characterized by an outer membrane that consists of three layers, as well as a total lack of cell wall (which renders these organisms insensitive to beta-lactam antimicrobial drugs). As certain species specifically infect the human genital tract and may even affect pregnancy outcomes, it is important to acknowledge their importance in human pathology.

But despite decades of study, many facets of the biology and clinical significance of genital mycoplasmas are still not completely understood for a myriad of reasons. Some of these include the high prevalence of these organisms in healthy individuals, the poor design of early studies, failure to take into account multifactorial aspects of certain maternal conditions and possible confounders, as well as unfamiliarity with their fastidious and complex nutritional requirements.

Cell Biology and Classification

The term “mycoplasma” is often used to refer to any members of the class Mollicutes, irrespective of the fact whether they truly belong to the genus Mycoplasma. They are considered to be eubacteria which evolved from clostridium-like predecessors by the process of gene deletion.

The saprophytic or parasitic nature of these organisms, as well as their sensitivity to the environment and their fastidious growth demands, are explained by their minute genome (i.e. less than 600 kilobase pairs for the smallest representative, Mycoplasma genitalium) and remarkably limited biosynthetic propensities.

As opposed to the tapered rodlike appearance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (which is a mollicute that gives rise to atypical pneumonia in humans), genital mycoplasmas are morphologically varied, being coccoid cells with an approximate diameter of 0.2 to 0.3 micrometers. Due to their lack of cell walls, they may often show pleomorphic characteristics and they cannot be stained by Gram stain.

Furthermore, light microscopy is ineffective for their detection because of their small cell mass; instead, typical colonies that grow on selective agar plates necessitate examination under a stereomicroscope in order to ascertain their morphologic features.

Also, the lack of a rigid cell makes genital mycoplasmas osmotically fragile, hence adequate maintenance of osmotic stability is required. Another issue is that they are very sensitive to desiccation, which significantly adds to the need for appropriate handling of clinical specimens before pursuing cultural isolation.

A Range of Species

The genital tract represents the main point of colonization for six distinct species – Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma fermentans, Mycoplasma penetrans, Mycoplasma spermatophilum and Mycoplasma primatum. The latter two are considered to be non-pathogenic for humans.

Although the mechanisms may be different between those species, all genital mycoplasmas have the ability to display antigenic shift, or vary the expression of immunogenic proteins on their cell surface. This is their way of avoiding the host immune response and the principal reason why they are able to persist for months (and even years) in the same host.

Each of the species has a somewhat different clinical profile. Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis are undoubtedly the most significant in terms of disease-inducing potential in pregnant women and neonates, although other species may contribute to such conditions to a lesser extent.

Mycoplasma genitalium was initially detected in men with urethritis, and it has been estimated to occur in up to 20% of men with urethritis, and up to 20% of women with urethritis or cervicitis. Mycoplasma fermentans became prominent as an opportunistic agent in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), but is also associated with chronic arthritic conditions.

Understanding the exact role of genital mycoplasmas in neonatal and perinatal disease as well as in other conditions will be facilitated if more physicians strive to make microbiological diagnoses when their presence is suspected, and patients will also benefit when the etiology of such infections is established in order to render appropriate therapy.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11839161

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17401188

- http://eknygos.lsmuni.lt/springer/599/271-288.pdf

- https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jpath/2014/183167/

- http://mmsl.cz/viCMS/soubory/pdf/MMSL_2013_4_1_WWW.pdf

- Mendoza N, Ravanfar P, Shetty AK, Pellicane BL, Creed R, Goel S, Tyring SK. Genital Mycoplasma Infection. In: Gross G, Tyring SK, editors. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media, 2011; pp. 197-202.

- Martin DH. Genital Mycoplasmas: Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma Species. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015; pp. 2190-2193.

Further Reading

- All Mycoplasma Content

- Diagnosis of Genital Mycoplasmas

- Treatment of Genital Mycoplasmas

- Effects of Mycoplasma Contamination on Research

- Mycoplasma Detection and Prevention in Cell Cultures

Last Updated: Feb 27, 2019

Written by

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović is a medical doctor (MD) with a Ph.D. in biomedical and health sciences, specialist in the field of clinical microbiology, and an Assistant Professor at Croatia's youngest university – University North. In addition to his interest in clinical, research and lecturing activities, his immense passion for medical writing and scientific communication goes back to his student days. He enjoys contributing back to the community. In his spare time, Tomislav is a movie buff and an avid traveler.

Source: Read Full Article