Q fever is a zoonotic or animal infection which spreads to humans, and occurs all over the world. The name was derived from “Query fever” because it was a mystery fever when first described, in an abattoir in Australia.

Later research showed that it was rickettsial in origin, and the organism responsible was first isolated by Burnet and Freeman. It is natural to wild animals, but transmitted to domestic animals and then to humans via ticks and other arthropods.

Symptoms

Q fever is often asymptomatic, but may also be an acute illness with fever, resolving spontaneously, manifesting as a bad headache behind the eyes, high fever of 104°F or more, violent chills, muscle aches, chest pain and a feeling of ill health.

Other acute stage manifestations include hepatitis or pneumonia. It may also follow a chronic course, usually characterized by endocarditis or inflammation and destruction of the inner smooth lining of the heart valves. Such a prolonged course is more often seen in patients who have a pre-existing heart valve disease, or are immunocompromised or pregnant.

Other serious complications include meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, and even death following endocarditis. If it occurs during pregnancy, the outcome may be miscarriage, preterm birth or low birth weight.

Transmission

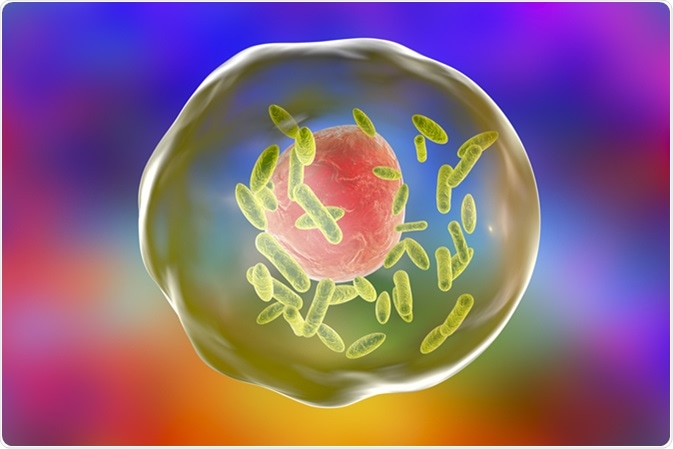

Infection with C. burnetii in animal hosts is typically asymptomatic but the organism is shed into the air over a long period of time, resulting in continued and prolonged spread of the infection.

In females, however, C. burnetii is excreted at high levels during parturition, with the placenta itself containing billions of rickettsiae. Thus, cows, ewes, goats, dogs and cats may often be the source of human infection, after they give birth, by releasing millions of bacteria into the air whence they are inhaled by humans.

It may be considered an occupational hazard in shepherds, cowherds, farmers, veterinary surgeons, workers in abattoirs, as well as dairy workers and laboratory staff who come in direct contact with infected bovines or pets, or while handling the cultures of these organisms.

Diagnosis and Management

Q fever is a public health problem in most of the world except in New Zealand. It is often missed because of the differences in clinical features, unless the patient is specifically examined for such a condition. The definitive diagnosis is made on the basis of serologic positivity for IgM and IgG antiphase II antibodies, which are present in the blood from about 2-3 weeks after infection. Chronic infection is diagnosed by detecting IgG antiphase I C antibodies at any titer above 1:800, using microimmunofluorescence. Isolation of the organism may be performed by cell culture.

Management of Q fever is done by protein synthesis inhibitor antibiotic therapy during the acute phase. However, chronic Q fever often requires multiple and prolonged antibiotic combinations, particularly if endocarditis is present. Fluoroquinolones and macrolides are also useful in indicated populations, but are not the first line of treatment.

Whole-cell vaccines against C. burnetii are effective when used, and are being considered for application in the high-risk population, but are difficult to obtain.

Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC88923/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27856520

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19875249

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3317737

Further Reading

- All Q Fever Content

- Q Fever Diagnosis

- Q Fever Symptoms

Last Updated: Feb 27, 2019

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article