Many Americans believe their communities are doing a good job meeting the needs of older adults, but white people may be better equipped than people of color to age within their communities, according to a new survey from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

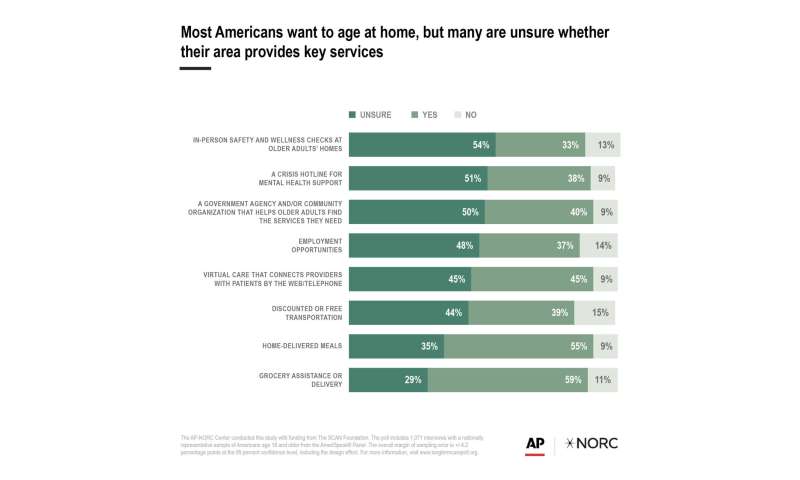

The poll finds more Americans think their area is doing well rather than poorly in providing access to resources and services for aging adults, including health care, healthy food, transportation and at-home support.

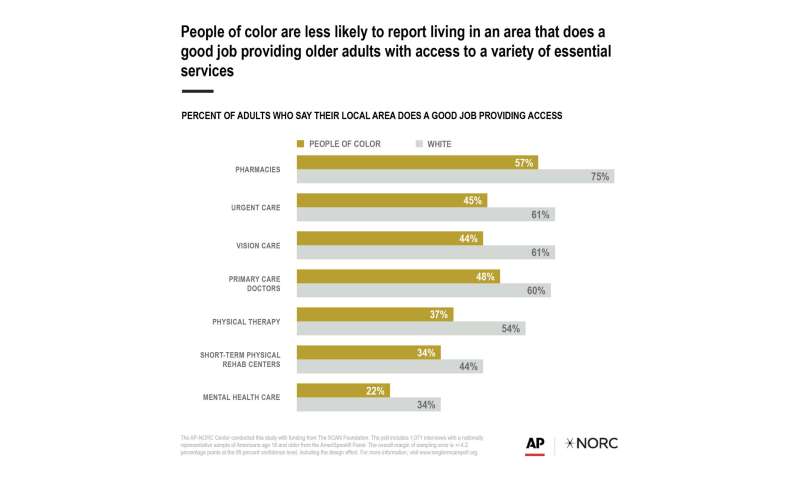

But white people are more likely than people of color to say their community does well in offering health care for older adults generally, as well as urgent care, primary care and physical therapy specifically. White Americans also are more positive than non-white Americans in rating their communities’ access to grocery stores, outdoor spaces, libraries and other amenities.

The poll finds community assessments also differ by household income, with Americans in lower-income households more likely than those earning higher incomes to say their communities are lacking across many resources and services.

Overall, 46% of Americans say their area is doing a good job providing access to health care for older adults, compared with 15% saying it does a poor job. Fifty-two percent of white people say their community does a good job, compared with 37% of people of color. Many people of color say either a poor job, neither or they don’t know. Uncertainty was an issue for many of the resources asked about on the poll.

Sarah Szanton, a professor at Johns Hopkins University’s nursing school, described aging as “the sum of people’s life experiences across the course of their life.”

“There’s certainly some randomness, there’s certainly some genetics involved, but, in general, aging is a health equity matter,” she said.

The poll finds just 34% of Americans say their communities do a good job offering in-home support services for older adults, compared with 14% saying it does a bad job. Another 31% say they don’t know. White people are somewhat more likely than people of color to say they have good in-home services accessible, 37% to 27%.

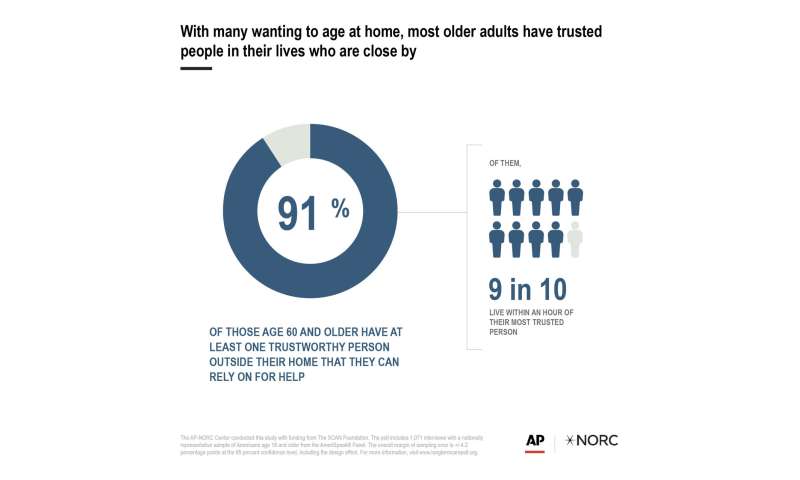

The new findings follow AP-NORC polling earlier this year that found a majority of Americans want the federal government to help Americans age in their own homes, which continues to be the option most prefer.

Dan Carrow has lived in New York City for more than 30 years, and he knows he wants to continue to live as close to a major city as possible as he gets older. But in his Washington Heights neighborhood, he feels the onus is on people to do research themselves to get health care and plan for the future.

“Because I live in New York, I have access to good health care. But you have to do all the research yourself,” said Carrow, who says he feels lucky to have family members in the health care industry. “I think if I didn’t have my family background and my education, I would be in bad shape.”

Carrow, an African American man, knows his neighborhood features world-class Columbia University—”the best medical care you can get”—but doesn’t think there is enough outreach to or understanding of the predominantly non-white neighborhood.

“I think what the medical profession has to start working on is building trust with individual people,” Carrow said. “Because people basically don’t trust doctors, especially people of color because of the past—our relationship we’ve had with them over the past century. So that’s how come many times people don’t go to a doctor till they’re like, you know, dancing around the doorway of death.”

Szanton compared funding for aging-in-community initiatives to funding for schools: localized and therefore disparate. Instead, she thinks initiatives should be statewide, “so that the people in the more low-income counties and cities don’t have fewer resources to be able to support aging-in-community initiatives.”

She pointed to decades of disinvestment in specifically majority African American neighborhoods as illustration of the problem.

“That snowballs, where the lack of wealth leads to more lack of wealth,” she said. “Then because community resources for aging are usually neighborhood or city or county based, those resources are also less.”

Jacqueline Angel, a professor of health, social policy and sociology at the University of Texas, said demographics factor into a person’s “physical, mental, social and even spiritual and emotional well-being.” And because disadvantages accumulate over time, Angel said, they are too wide for aging programs—Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security—to fully close the gap.

“One has to provide the resources that will be able to curb the disparities in health, income and overall quality of life,” she said. “It’s more critical now than ever to be able to do that given the pace of our aging racial minority population.”

___

Source: Read Full Article