Ask Danielle Palmieri when her newborn son contracted RSV, and she doesn’t give a season or even a month. She knows the exact day.

Nov. 6, 2022. It was her 4-year-old daughter’s birthday party at their Upper St. Clair home, and also the day she saw her 3½-week-old son, Cameron, begin “belly breathing”—where the undulations of chest and belly movements go out of sync as a sign of respiratory trouble—with a hacking cough and “so much congestion.”

Because she’s a pediatric nurse, she noticed more subtle clinical signs of potential distress called retractions, where skin covering the ribcage is sucked in (slightly or profoundly) with each inhalation.

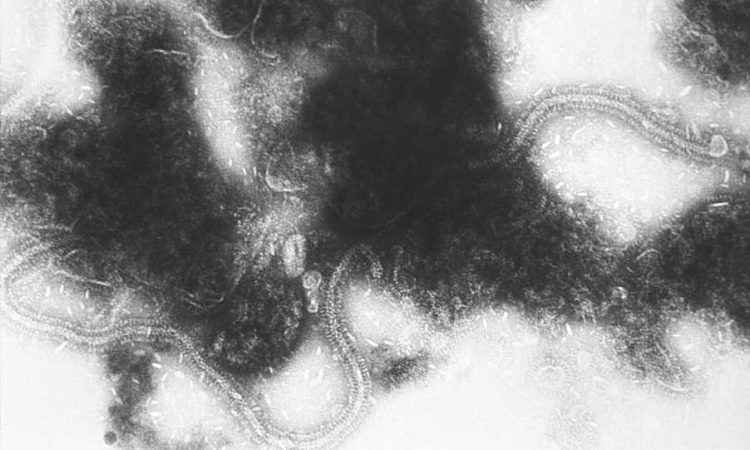

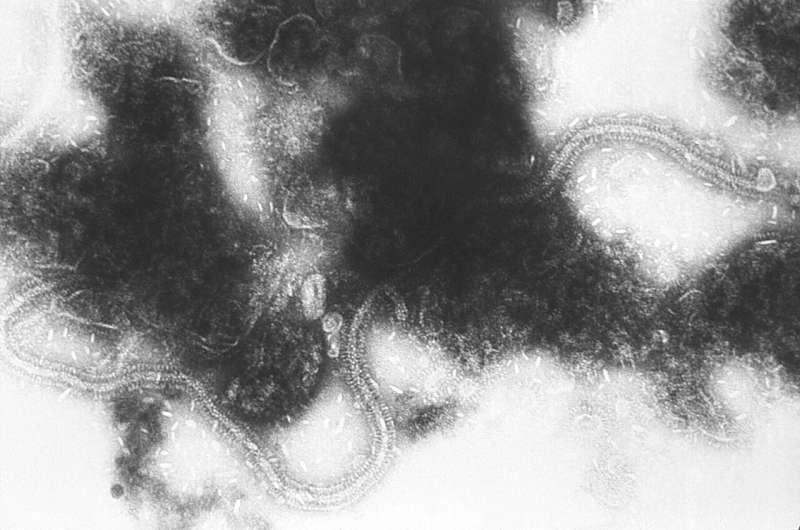

Her kindergarten-aged daughter had been sick when they brought the baby home. They had her wash her hands frequently, wear a mask near her baby brother and even change her clothes after school, but that wasn’t enough to prevent what was later diagnosed as RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus.

“It was so stressful,” she said. “I was worried that at any time it would take a turn for the worse, and we’d have to go to Children’s Hospital.”

She and her husband purchased monitoring and suction devices to manage the acute phase of his illness, which lasted a week or two. But the cough and congestion lasted about six weeks total, making her sleep deficit “times 20” even compared to ordinary newborn sleep chaos.

Despite the intensity of her own situation with Cam, she “can’t imagine” the anxiety families feel when their young children are hospitalized with RSV.

In the U.S., those families account for 58,000 to 80,000 hospital admissions. Or they did, until the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two new tools in the RSV-fighting toolkit.

With a vaccine for pregnant women capable of conferring protection to babies before they ever leave the womb and a monoclonal antibody able to protect children under 8 months of age for six months, those numbers are bound to drop.

But considering how new those weapons are—approved in July for babies and August for moms—the collaboration they require and that pesky issue of supply, medical providers have plenty of work ahead, with the beginning of RSV season looming less than one month away.

1 is greater than 10

Palmieri’s situation with Cam would rattle any mom. The number of kids landing in the hospital each year because of RSV sounds huge. But considering that every child in the world contracts RSV at least once, and maybe twice, before their second birthdays, these families are in the minority.

“The majority of kids, more than 95%, will have no problem with RSV other than having a profuse runny nose, maybe a little fever and a little bit of a cough,” said Joe Aracri, Allegheny Health Network Pediatric Institute system chair of pediatrics. “A small group of those kids will end up wheezing a little bit. They may end up coughing a lot, to the point of throwing up. But most will not be in respiratory distress.”

It’s “1% or even less” who end up needing supplemental oxygen, hospital-caliber nasal suction, IV fluids or more, he said.

For children born prematurely, or with heart or lung disease or a host of other differences that might put them at higher risk for severe outcomes, RSV protection has existed since 1998 with a monoclonal antibody injection called Synagis.

Rather than being a “vaccine” that teaches the immune system how to create antibodies to fight that particular virus, it simply gives those antibodies. And because of its nature, it allows for those kids to still be exposed to the virus—even catch it, which does inform the immune system—but prevents severe disease.

Synagis is still on the market, and is still protecting these vulnerable kids through the first two years of their lives.

If that sounds like two injections, think again. It’s 10.

“Not having to come in every month for the five months of RSV season is a big advantage,” said pediatrician and public health specialist Marian Michaels, who works on UPMC Children’s Hospital’s infectious disease team. “But it’s expensive,” at more than $1,000 per injection, depending on the pharmacy. “It’s cumbersome. Accordingly, we used it for only the highest-risk babies.”

This is where the new monoclonal for kids is different.

Beyfortus, developed by AstraZeneca and marketed in the U.S. by Sanofi, is one intramuscular injection per season, offering 70-75% protection versus a placebo. Per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions’ recommendations, every American baby will be encouraged to receive this vaccine before 8 months of life, which will provide six months of protection. For more medically complicated babies, that coverage will repeat for one additional year.

And like Synagis, because it’s simply handing the immune system weapons rather than teaching it to make them, the side effect profile is very friendly.

“This therapeutic is incredibly safe,” Aracri said. “There are minimal side effects other than pain at the site of injection. We really think this is going to be a game-changer during RSV season for a lot of these babies.”

Second, not second place

Just as American pediatricians were getting comfortable with the idea of Beyfortus, the FDA dropped a (welcomed) bomb last month.

The government body approved Pfizer’s Abrysvo, a true vaccine against RSV given to pregnant women between 32 and 36 weeks gestation. It can cross the placenta and provide coverage to babies before they ever see the outside world, reducing the risk of serious disease by about 82%, as measured within 90 days post-birth. And since diseases like RSV can be more severe during pregnancy, it protects moms too.

It’s a little sci-fi, but with plenty of precedent. This is exactly the mechanism exploited by vaccinating moms against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis/whooping cough (in a formulation known as Tdap), influenza and COVID-19.

All of these vaccines are considered safe based on observational data, but in a coup for would-be Abrysvo patients, this one was tested directly on pregnant women—7,200 of them.

“This should lead to providers recommending the vaccine, having a higher level of confidence that when used during pregnancy, it’s not going to produce adverse outcomes, and quite the contrary,” said Richard Beigi, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center obstetrician and president of UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital. “It should arm the providers with more confidence to give a stronger recommendation.”

Art and science

Celebration over the now-overflowing toolbox against RSV is understandable, especially given last year’s “tripledemic” of flu, RSV and COVID-19. But when the adrenaline wanes, there are unavoidable questions.

Chief among those: How will pediatricians and obstetricians collaborate? And since “8 months” doesn’t align with any traditional infant check-up schedule, when will they actually receive the monoclonal?

“I don’t think this is going to be black and white,” Michaels said. “Black and white makes things much easier in terms of having recommendations go out, but in fact, I think there are nuances, and we need to be able to have a little bit of wiggle room for families.”

Both UPMC and AHN—and hospital systems across the country—are still deciding exactly how their cogs will align, but they agree the approach will be one of both art and science, though none of that can happen without adequate supply.

Speaking for AHN Pediatrics Institute on the availability of Beyfortus, Aracri said, “When I spoke with the manufacturer, they feel like they’ll have no problem meeting demands here. The therapeutic—we know, we hope—will be ready hopefully by Oct. 1 for us.”

Speaking for UPMC on the same topic, Michaels said, “We don’t have the medicine yet. I keep looking at the calendar, and we’re getting very close to RSV season. The company is really making a very big effort to try to make it available for this season. I’m cautiously optimistic, but there are some logistics we still need to work on.”

Abrysvo must be considered by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) before clinical use recommendations are doled out. After that, highly respected professional organization the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will also weigh in before American OBs will have all the information they likely wish to, a process that will last “a few months,” according to Beigi.

But assuming there are no drastic changes, a baby’s protection status from RSV will involve a cluster of facts: whether mom received Abrysvo, whether baby received Beyfortus, when those protections occurred and the time of year relative to RSV season.

Sometimes, all of those logistics will align perfectly, and those babies might never need an additional injection because mom, and lucky timing, took care of it. For the rest, physicians are weighing whether Beyfortus should be available in newborn nurseries within hospitals, versus waiting for checkups in pediatricians’ offices, versus “shot clinic” environments, like those seen yearly for influenza vaccines.

Some of that will depend on cost and insurance.

The FDA has already noted that Beyfortus will be the first monoclonal antibody available via Vaccines for All, a federally funded program that provides vaccines/therapeutics to children whose insurance (or lack thereof) wouldn’t provide for them. But when it comes to administration in newborn nurseries, Michaels feels cost might be a factor relative to reimbursement, since she understands the monoclonal will cost less than Synagis, but will still be “substantial” and “several hundred dollars.”

Despite these brand-new tools, Michaels simultaneously advocates for RSV-preventing strategies with far less fanfare: hand-washing, avoiding sick people and staying up-to-date on other recommended vaccines.

They’re certainly effective, but plenty of times, they aren’t enough, as they weren’t for the Palmieri family.

As a mom, she watched her newborn son work to clear an incredible amount of congestion compared to his tiny respiratory passages. As a pediatric triage nurse, she guides parents through middle-of-the-night calls sometimes about the very same thing, which is why she couldn’t be more excited for her youngest patients and their families to potentially dodge this illness altogether.

But getting there is certainly a few steps away.

“There’s a strong case to make that it’s really going to be a two-pronged approach, really trying to maximize immunization in the mother, and figure it out from there,” Beigi said. “But I really think part of the ACIP, and subsequently the ACOG’s job, will be managing those two preventative treatments, which is a really great position to be in.

“It’s a great problem to have.”

2023 PG Publishing Co.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Source: Read Full Article