Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

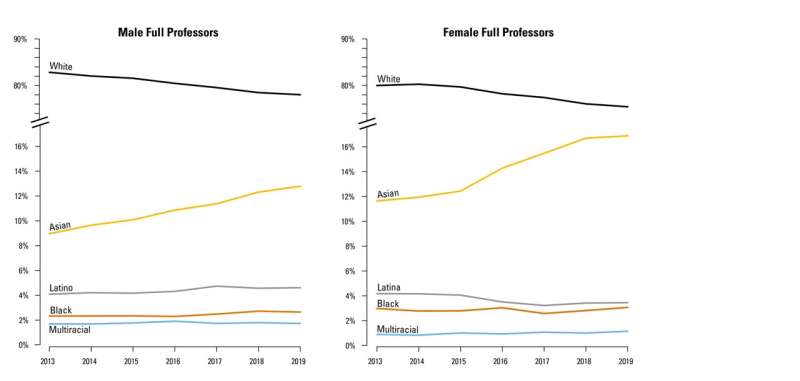

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits.

Women from these underrepresented groups were even more absent from leadership. During the study window, only one Black woman and one Latina woman ascended to the role of department chair, up from zero prior to 2015, suggesting that the combination of gender with race or ethnicity deepened the disadvantages these surgeons faced when trying to rise through the ranks.

“There are a lot of talented surgeons of different races, ethnicities and genders who do wonderful work and are being underrecognized or not recognized at all. And that’s contributed to a lot of frustration,” said study senior author Jose Trevino, M.D., chair of surgical oncology and associate professor of surgery at the VCU School of Medicine and surgeon-in-chief at VCU Massey Cancer Center.

In 2019, the vast majority of chairs and full professors were white, occupying about three quarters of these positions. Black and Latinx surgeons held about 3% to 5% of the full professorships and chairs—clear underrepresentation considering the overall demographics of the country.

“I don’t think it’s a matter that they don’t aspire to these positions,” said study lead author Andrea Riner, M.D., M.P.H., a surgical resident at the University of Florida College of Medicine. “And I think many of them are truly qualified to lead.”

Over the six-year study period, the share of surgery department chairs and full professorships held by white doctors decreased by 4 to 5 percentage points, but it was Asian faculty who filled the void, rising by 4 percentage points over the same timeframe.

Male Black and Latino chairs actually lost ground during the six-year study period, dropping 0.1 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively.

According to the authors, one way to promote success for traditionally underrepresented groups is sponsorship—meaning someone in a position of power serves as an advocate for someone else who doesn’t have the same level of influence.

“Having that person speak up for you and say you are deserving of whatever position you’d like to hold is really powerful,” Riner said. “As a profession, we need to be a little more cognizant or intentional about sponsoring diverse people within our departments.”

Mentorship and allyship are also important for leveling inequities in surgical leadership. Similar to sponsors, mentors provide expertise and support, though they may not have the clout to create opportunities for their mentees the way a sponsor could. Allyship is broader still. Anyone can be an ally, regardless of career level, so long as they lend support.

And the simple act of representation helps too. When students and residents see leaders who look like them, aspiring to those positions seems more realistic. But when female and minority trainees see a glass ceiling, they may be more likely to choose a different career.

Source: Read Full Article