With implications for the transmission of diseases like COVID-19, researchers have found that ordinary conversation creates a conical ‘jet-like’ airflow that quickly carries a spray of tiny droplets from a speaker’s mouth across meters of an interior space.

“People should recognize that they have an effect around them,” said Howard Stone, the Donald R. Dixon ’69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Princeton University. “It’s not just around your head, it is at the scale of meters.”

Although scientists have not yet fully identified the transmission mechanisms of COVID-19, current research indicates that people without symptoms could infect others through tiny droplets created when they speak, sing or laugh. Stone and co-lead researcher Manouk Abkarian, of the University of Montpellier in France, wanted to learn how widely and quickly exhaled material from an average speaker could spread in an interior space.

“Lots of people have written about coughs and sneezes and the kinds of things you worry about with the flu,” Stone said. “But those features are associated with visible symptoms, and with this disease we are seeing a lot of spread by people without symptoms.”

In an article published Sept. 25 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers concluded that for interior activities, normal conversations can spread exhaled material at least far as, if not beyond, social distancing guidelines recommended by the World Health Authority (1 meter) and U.S. officials (2 meters.) The work examined particle flow in an interior space without good ventilation.

Stone and Abkarian stressed that they are not public health experts and are not making medical recommendations. However, they said public health officials should consider the aerodynamic movement of aerosolized particles generated by speech alone already as an important factor for directed spreading.

“It certainly highlights the importance of ventilation,” Stone said. “Especially if you have an extended conversation.”

The researchers also said that while masks do not completely block the flow of aerosols, they play a critical role in disruption of the ‘jet-like’ air flow from a speaker’s mouth, preventing the quick transport of droplets on large length scales bigger than 30 cm.

“Masks really cut this flow of tremendously,” Stone said. “This identifies why (most) masks play a big role. They cut everything off.”

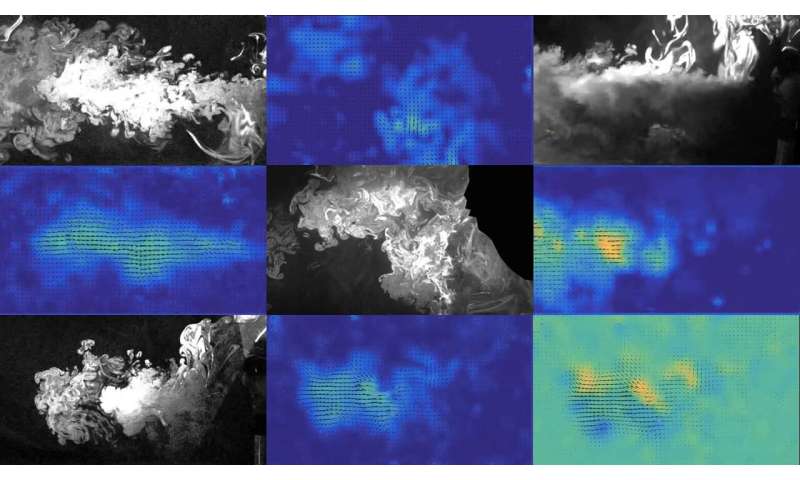

The researchers specialize in fluid dynamics, which describes the movement of liquids and gasses. Using a high-speed camera, they film the movement of a mist of tiny droplets illuminated by a laser sheet in front of a person speaking several different phrases adjacent to the sheet. The phrases ranged from short statements like “we will beat the corona virus” to nursery rhymes including “Peter Piper picked a peck” and “Sing a song of six pence.” The researchers selected the phrases to include different sounds that affect turbulent flows in a speaker’s exhalation.

The researchers found that plosive sounds like ‘P’ create puffs of air in front of the speaker while a conversation created what the researchers called a “train of puffs.” Each puff creates a small vortex of air in front of the speaker, and the interaction of these vortices creates a cone-shaped ‘jet-like’ airflow from the speaker’s mouth. The researchers found that this airflow could easily and very quickly carry tiny particles away from the speaker.

Abkarian said that even a short phrase can move the particles past the 1-meter distancing recommended by the World Health Organization in a matter of seconds.

The researchers said the distance depends in part on the duration of the conversation. Someone speaking for more time will send particles farther. They said that the 6-foot distancing rule may not be a sufficient barrier in an interior space without good ventilation.

“If you speak for 30 seconds in a loud voice, you are going to project aerosol more than six feet in the direction of your interlocutor,” Stone said.

In the paper, the researchers found that aerosols ejected during speech typically reached the 2-meter distance in about 30 seconds, and over that distance the aerosols’ concentration diluted to about 3 percent of the original volume. It was beyond the paper’s scope to say whether the dilution was sufficient to protect against infection, although the researchers noted that many will find this concentration to be higher than expected. The researchers said they hoped the information could help public health officials to make that determination. They also noted that longer conversations had the potential to spread more material and spread the virus over a larger distance.

“However, more extended discussions, and meetings in confined spaces, mean that the local environment will potentially contain exhaled air over a significantly longer distance,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers said the experiment showed that a social distance of 6 feet (2 meters) did not work like a wall to protect people. Over time, conversations can cause material to move past the distance, particularly inside buildings.

Source: Read Full Article