A research team led by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) has made a key advance in understanding how predictive processing is enabled/implemented in the human brain and shows that it may be modulated through non-invasive electrical stimulation.

The study was conducted by a team from the Institute for Neuroscience (INc-UAB) and the Department of Clinical and Health Psychology of the UAB, the Mayo Clinic, and the University of Munich, and was directed by Lorena Chanes, associate and ICREA Acadèmia professor. It was recently published in the journal Cerebral Cortex.

The human brain works predictively, constantly anticipating sensory input based on an internal model of the world based on past experiences. Predictions are compared to actual sensory input, and the difference is used to update the model if needed, in order to minimize future errors.

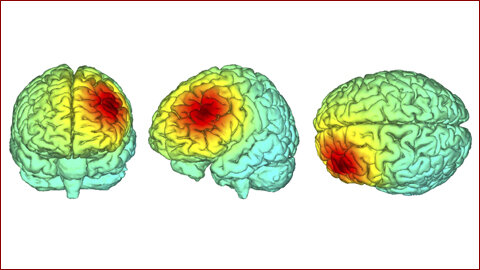

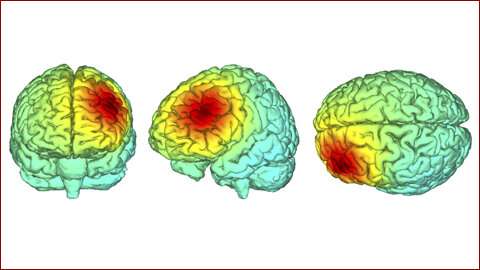

According to existing literature, predictive processing is implemented in the brain with signals that “travel” as waves through several parts of the brain cortex on different frequency bands: beta oscillations (13–30 Hz) for predictions and gamma oscillations (30–90 Hz) for prediction errors. In the published study, researchers used non-invasive electrical stimulations on a left prefrontal cortex area to modulate these signals selectively and test their effect on an emotional prediction and social perception task.

The study involved 75 participants, who were asked to predict the facial expressions of a variety of individuals reacting to different emotional contexts evoking happiness, sadness or fear. During the task, researchers applied non-invasive electrical stimulation to the participants using an electrodes helmet, and at the same time recorded brain activity with electroencephalography.

Researchers observed that stimulation at a frequency of 20 Hz (within the beta oscillations range) had an effect on facial expression predictions, making them more stereotypical: when stimulated, participants tended to expect, to a greater extent than when not, a smiling expression in a situation that evoked happiness, a pouting expression in a situation evoking sadness, and a face with its eyes wide open in a situation evoking fear. The impact of electrical stimulation was also observed on electroencephalography, which showed an increase in brain activity on the frequency band of the frequency used in the area where it was applied.

“This result, together with the absence of a modulation at a different frequency, demonstrates that predictive processing is coded in the brain on specific frequency bands and that it may be modulated non-invasive ‘at will’ in order to ‘artificially’ modify behavior in a task,” Lorena Chanes points out.

The study provides new information on the neural basis of predictive processing, setting the stage for understand how it can be disrupted on brain-related conditions and, potentially, restored using non-invasive methods. “An increasing number of conditions are being described in terms of predictive processing disruptions, as seen for example in a previous study related to depression. In this sense, although the effect observed is small, it may open the door to developing therapies based on these types of modulations,” the UAB researcher adds.

The authors of the study also point out that their observations could extend beyond the area of social perception. “Predictive processing is a fundamental mechanism of brain function and, thus, its implications go beyond the field of study of facial expressions and social perception. It is possible that similar modulations to the ones observed in this study may be observed on other cognitive tasks. This will be something to explore in future research,” the researchers state.

More information:

Metodi Draganov et al, Noninvasive modulation of predictive coding in humans: causal evidence for frequency-specific temporal dynamics, Cerebral Cortex (2023). DOI: 10.1093/cercor/bhad127

Journal information:

Cerebral Cortex

Source: Read Full Article