Young babies make many squeals, vowel-like sounds, growls and short, word-like sounds such as “ba” or “aga.” Those precursors to speech, or protophones, are later replaced with early words and, eventually, whole phrases and sentences. While some infants are naturally more talkative than others, a new study reported in iScience on May 31 confirms that there are differences between males and females in the number of those sounds.

In general, they found that male infants babble more than female infants in the first year. While the research confirms earlier findings from a much smaller study by the same team, they still come as a surprise. That’s because there’s a common and long-held belief that females have a reliable advantage over males in language. They also have interesting implications for the evolutionary foundations of language, the researchers say.

“Females are believed widely to have a small but discernible advantage over males in language,” says D. Kimbrough Oller of the University of Memphis, Tennessee. “But in the first year, males have proven to produce more speech-like vocalization than females.”

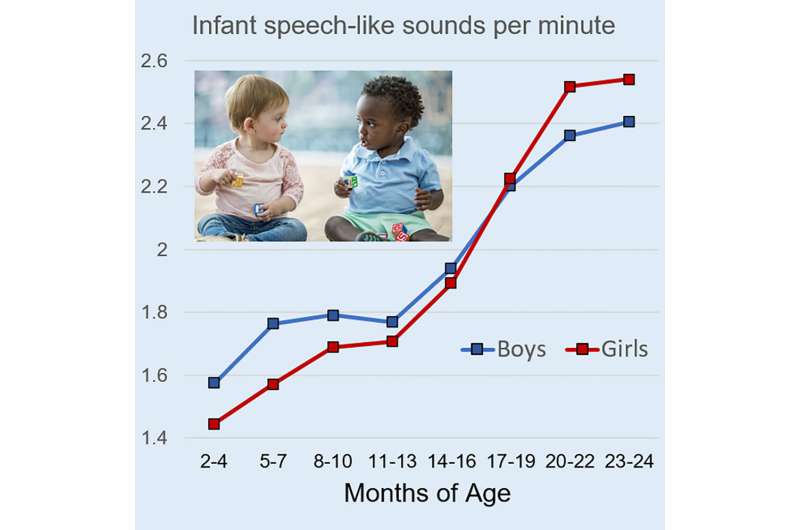

Male infants’ apparent early advantage in language development doesn’t last however. “While boys showed higher rates of vocalization in the first year, the girls caught up and passed the boys by the end of the second year,” Oller says.

Oller and colleagues hadn’t meant to look at sex difference at all. Their primary interest is in the origins of language in infancy. If they’d had to guess, they’d have predicted female infants might make more sounds than males. But they got the same result in an earlier paper reported in Current Biology in 2020.

In the new study, they looked to see if they could discern the same pattern in a much larger study. Oller says that the sample size in question is “enormous,” including more than 450,000 hours of all-day recordings of 5,899 infants, using a device about the size of an iPod. Those recordings were analyzed automatically to count infant and adult utterances across the first two years of life.

“This is the biggest sample for any study ever conducted on language development, as far as we know,” Oller says.

Overall, the data showed that male infants made 10% more utterances in the first year compared to females. In the second year, the difference switched directions, with female infants making about 7% more sounds than males. Those differences were observed even though the number of words spoken by adults caring for those infants was higher for female infants in both years compared to males.

The researchers say it is possible male infants are more vocal early simply because they are more active in general. But the data do not seem to support that given that the increased vocalizations in male infants go away by 16 months while their greater physical activity level does not. But the findings might fit with an evolutionary theory that infants make so many sounds early on to express their wellness and improve their own odds of surviving, Oller suggests.

Why, then, would male infants be more vocal than females in the first year and not later? “We think it may be because boys are more vulnerable to dying in the first year than girls, and given that so many male deaths occur in the first year, boys may have been under especially high selection pressure to produce vocal fitness signals,” Oller says. By the second year of life, as death rates drop dramatically across the board, he added, “the pressure on special fitness signaling is lower for both boys and girls.”

More study is needed to understand how caregivers react to baby sounds, according to the researchers.

“We anticipate that caregivers will show discernible reactions of interest and of being charmed by the speech-like sounds, indicators that fitness signaling by the baby elicits real feelings of fondness and willingness to invest in the well-being of infants who vocalize especially effectively,” Oller says. “We wonder how caregivers will react to speech-like sounds of boys and girls. But they may have to be told which infants are which, because we don’t even know if sex can be discerned in the vocalizations alone.”

More information:

D. Kimbrough Oller, Sex differences in infant vocalization and the origin of language, iScience (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106884. www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext … 2589-0042(23)00961-6

Journal information:

Current Biology

,

iScience

Source: Read Full Article