How microbiota—microbes that live on human surfaces—impact cancer development and therapy has become an expansive area of research.

Although a few associations have garnered support from the scientific community, such as hepatitis B and C affiliated with development of liver cancer, studies describing microbiota’s disease-causing and therapeutic contributions with many cancers are still very much in the early stages, according to a recent review paper by three infectious diseases and cancer experts from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, the center’s Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The write-up was published in the journal Nature Cancer.

Comprehensive studies are needed to further understand how the microbiome is driving some of the biology underlying cancer development and cancer responses to treatment, the authors say.

“We’re at a point in the field of microbiome studies as they relate to cancer where there’s now a large body of data showing associations, and a smaller amount of data showing mechanisms and direct effects promoting tumor development, but there are more questions than answers,” says study co-author Jessica Queen, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins. “We focused our review on what we know now and the remaining critical gaps to move forward.”

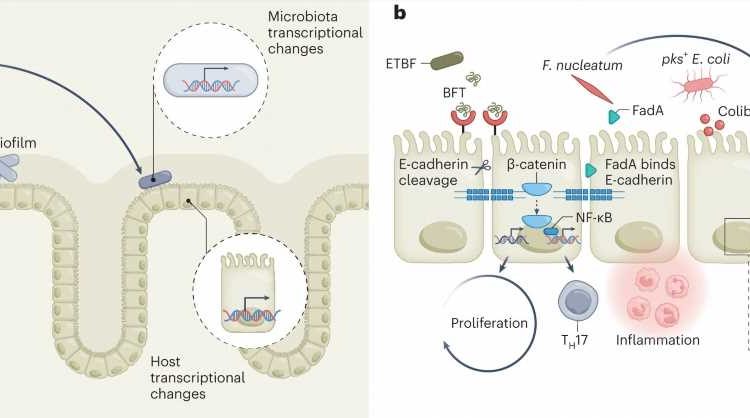

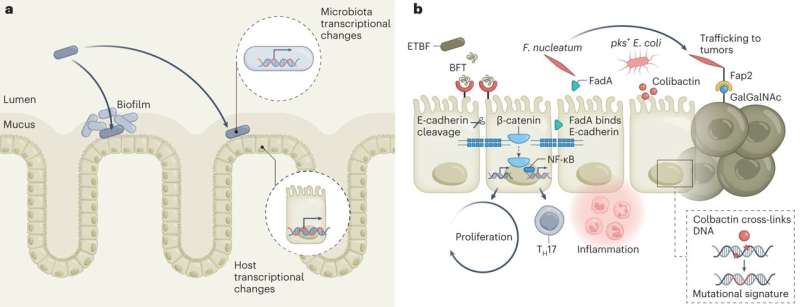

The paper reviewed published studies in areas such as biofilms and other mechanisms promoted by the microbial community, microbes as modulators of the immune system, microbiota metabolites that potentially contribute to cancer development, the impact of diet as a modifier of metabolites, microbiota effects on the host genome and microbiota modulation as therapy for cancer, such as the use of human fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), prebiotics and probiotics

Several hurdles need to be overcome to advance the field, the authors say. One is inconsistency between some studies of microbes that have been associated with certain cancers or therapeutic modalities, likely caused by technical differences in DNA extraction or sequencing practices. Another is the gaps between computational or mouse models and translation to humans, with few rodent studies validated in humans.

Investigators in the field have been quick to publish their work, adds study co-author Cynthia Sears, M.D., Bloomberg~Kimmel Professorship of Cancer Immunotherapy and professor of medicine. Two FMT studies, for example, generated intense interest, but only two patients responded well to the therapy among 25 given FMT.

“It’s time to settle down and have a more comprehensive, prospective, thoughtful plan to understand what matters, such as through longitudinal, well controlled human studies incorporating microbiome science,” says Sears, who is also the microbiome program leader at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“Expanding the scope of new clinical trials is one approach to speed the development of improved insights and, ultimately, tools to prevent, diagnose and treat cancer.”

Bacterial function is an area on which there could be more focus, adds co-author Fyza Shaikh, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins. “The metabolites offer an opportunity to focus on the output of an entire bacterial community and identify any redundancies that might be present between different bacteria that might do the same thing,” Shaikh says. “That has really been inconsistent across a lot of current studies.”

Future studies should focus on collecting clinical data, including about dietary and medication exposures as key modulators of the microbiome, the authors say.

More information:

Jessica Queen et al, Understanding the mechanisms and translational implications of the microbiome for cancer therapy innovation, Nature Cancer (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s43018-023-00602-2

Journal information:

Nature Cancer

Source: Read Full Article