The COVID-19 pandemic has irreversibly altered our lives in many ways. However, available COVID vaccines are effective against (symptomatic) severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, hospitalizations, and even death. Despite a diminishing protective effect against infection and onward transmission after vaccination, and a slightly diminished effect with the Delta variant compared to the Alpha variant, protection against severe outcomes remains high.

Risky behavior

Although vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 has been well documented physiologically, behavioral effects have been little studied. As a result of vaccination, personal safety gains are offset by increases in risky behavior, including socializing, commuting, and working outside the home. In addition, because contacts with other individuals drive transmission of SARS-CoV-2, vaccine-related risk compensation may amplify this problem.

In a new study, researchers found that behaviors were overall unrelated to personal vaccination but – adjusting for variation in mitigation policies – were responsive to the level of vaccination in the wider population. Individuals in the UK were risk compensating when rates of vaccination were rising. This effect was observed across four nations of the UK, each of which varied policies autonomously.

People who have been vaccinated are often less concerned about contracting SARS-CoV-2, becoming critically ill from the infection, or spreading the disease if infected. Hence, people are now lowering their guards and may end up socializing in large gatherings, traveling across borders, and may practice social distancing less frequently. This less cautious behavior is known as risk compensation or the Peltzman effect.

Earlier research on risk compensation associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rendered contradictory outcomes—with reporting some reporting in favor of behavioral changes while others against.

The study

The current study published on the medRxiv* preprint server attempted to assess risk-compensatory behaviors and contacts in the United Kingdom (UK) following COVID-19 vaccination. However, risk compensation may have substantial short- and medium-term public health consequences, particularly if individuals or their unvaccinated household members change their behavior prior to full vaccination. Therefore, it is critical for public health divisions and policy development authorities to know the extent to which post-vaccination behaviors are risk-compensatory.

Considering this, authors evaluated behaviors of individuals in response to COVID-19 vaccine uptake by themselves, their vulnerable household members, and in their specific geographical areas by analyzing data obtained from the National Statistics (ONS) COVID-19 Infection Survey (CIS).

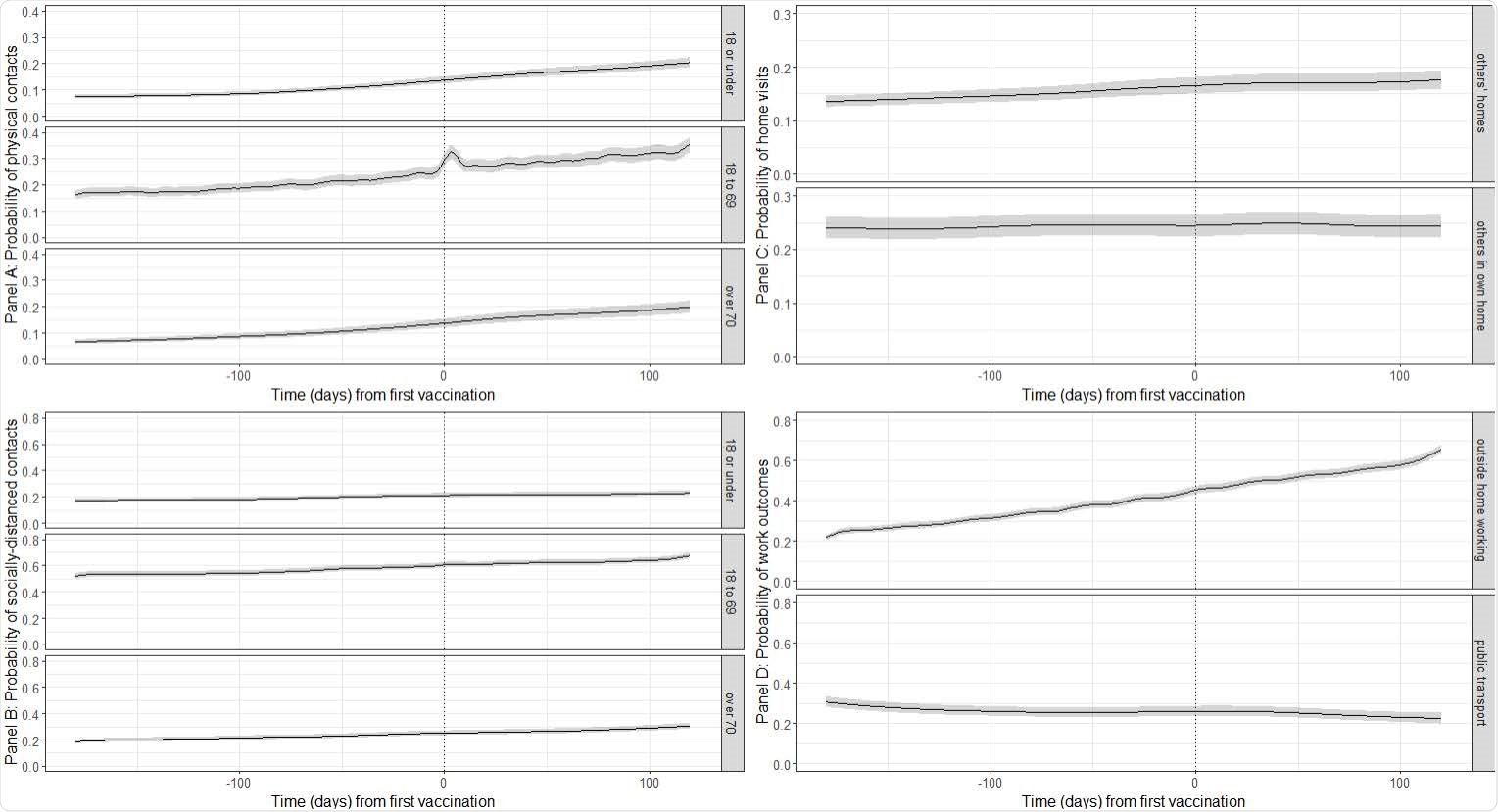

Here, the authors studied the probabilities of behavioral alterations in physical or socially-distanced contacts with individuals outside of the home, during visits to others' homes or of others to one's own home, at the workplace, and while on public transport.

This survey comprised multiple cross-sectional household surveys with extra serial sampling and longitudinal follow-ups. Participants selected were 18 years olds or those who self-reported a long-term health condition (in the UK, those with underlying health concerns aged 16 years and above were given priority over those 65-year-olds and above).

Patients were questioned about their vaccination status, including the type of vaccine, number of doses, and the date of administration(s). The administrative data of the National Immunisation Management Service (NIMS) were also connected to survey participants from England.

10 behavioral outcomes

The study recorded ten behavioral outcomes that were self-reported by individuals:

- The number of physical contacts, e.g., handshake, personal care, including with personal protective equipment, with individuals aged <18 years old in the past 7 days;

- The number of physical contacts with individuals aged 18-69 years old in the past 7 days;

- The number of physical contacts with individuals aged 70 years and over in the past 7 days;

- The number of socially distanced contacts, worded as "direct, but not physical, contact," with individuals aged <18 years old in the past 7 days;

- The number of socially distanced contacts with individuals aged 18-69 years old in the past 7 days;

- The number of socially distanced contacts with individuals aged 70 years and over in the past 7 days;

- The number of times the participant spend one hour or longer inside their own home with someone from another household in the past 7 days;

- The number of times the participant spent time one hour or longer inside the building of another person's home in the past 7 days;

- Among those that reported engagement in work or studying: mode of travel to work/place of education (grouped as public transport versus other for the current analyses) in the past 7 days; and

- Among those that reported engagement in work or studying, the primary work/study location over the past week was recorded.

There were no differences in the gradients of pre-and post-vaccination periods in terms of reporting any socially-distanced contacts with others outside the household, the probability of reporting any visits to others' homes or others' visits to the individual's own home, or the probability of reporting working from home and using public transport for commuting.

Moreover, this was the case across behaviors accounted for concerning the comparison of post-vaccination periods with pre-vaccination. Hence, there was no evidence of a behavioral response to being vaccinated on these outcomes.

It was observed that, since the first vaccination dose, there appeared to be a general rise in the inclination towards socializing – especially, through physical interactions, having at least one socially-distanced contact outside their household or working outside of the home, especially after the high-risk family members had been vaccinated.

Furthermore, the probability of working outside of the home increased concurrently with increasing population-level vaccination. Meanwhile, the probability of using public transport for work travel declined concurrently with increasing population-level vaccination uptake—probably due to an increased preference for private transport.

A major advantage of this study was the incorporation of a robust, nationally representative, random sample from the UK. In addition, this work covered a wide range of behavioral outcomes, which facilitated a better understanding of behavioral changes under various public health mitigation measures. On the flip side, the survey's shortcomings were that it was dependent on self-reported behaviors, and in such scenarios, people often underreport socially desirable behaviors.

Overall, the authors have demonstrated for the first time the behavioral response to COVID-19 vaccination on a population level. Further, the findings imply that during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, population-rate-based risk compensating may have dominated behaviors in the UK.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Buckell, J., Jones, J., Matthews, P., et al. (2021), "COVID-19 vaccination, risk-compensatory behaviours, and social contacts in four countries in the UK", medRxiv* preprint, doi: 10.1101/2021.11.15.21266255, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.11.15.21266255v1

Posted in: Men's Health News | Medical Research News | Women's Health News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Education, Pandemic, Personal Protective Equipment, Public Health, Research, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Syndrome, Vaccine

Written by

Nidhi Saha

I am a medical content writer and editor. My interests lie in public health awareness and medical communication. I have worked as a clinical dentist and as a consultant research writer in an Indian medical publishing house. It is my constant endeavor is to update knowledge on newer treatment modalities relating to various medical fields. I have also aided in proofreading and publication of manuscripts in accredited medical journals. I like to sketch, read and listen to music in my leisure time.

Source: Read Full Article