Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), resides in mucous membranes, making it easy to detect viral load in the nasal cavities.

An international group of researchers has characterized the immunological and diagnosis characteristics of patients who may have or are confirmed with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team found a distinct nasal cytokine profile that could help identify patients at risk for high inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Our study provides insights on the cytokine responses in the nasal mucosa following SARS-CoV-2 infection in severe COVID-19 patients and the potential importance of additional confirmatory antibody tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 PCR-negative patients with high clinical suspicion of COVID-19,” wrote the researchers.

The study “Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a distinct nasal cytokine profile” is available as a preprint on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

.jpg)

Classifying the type of patient admitted for respiratory infection

From April 21st to September 25th, 2020, the team collected nasal mucous samples from 87 patients who presented to a low-income sub-Saharan African hospital with a severe acute respiratory infection. Following a PCR test, 41 patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The other 46 patients were NAAT negative, but the team reclassified them based on their immunoglobulin G (IgG) status against spike protein 2. A total of 25 patients were IgG positive, and 21 patients were IgG negative. Controls included 25 healthy volunteers.

Based on participant information, patients who tested positive for COVID-19 and had to be admitted to the hospital were a median of 50 years and older, 63% more likely to have been administered dexamethasone, and 78% more likely to have received a beta-lactam antibiotic.

Patients who were PCR-confirmed for COVID-19 were 93% more likely to survive but also more likely to stay longer at the hospital than people who were PCR negative but IgG positive. Patients who were PCR negative but IgG negative spent the least amount of time in the hospital at a median of 6 days and had a survival rate of 57%.

Nasal mucosa shows altered cytokine levels

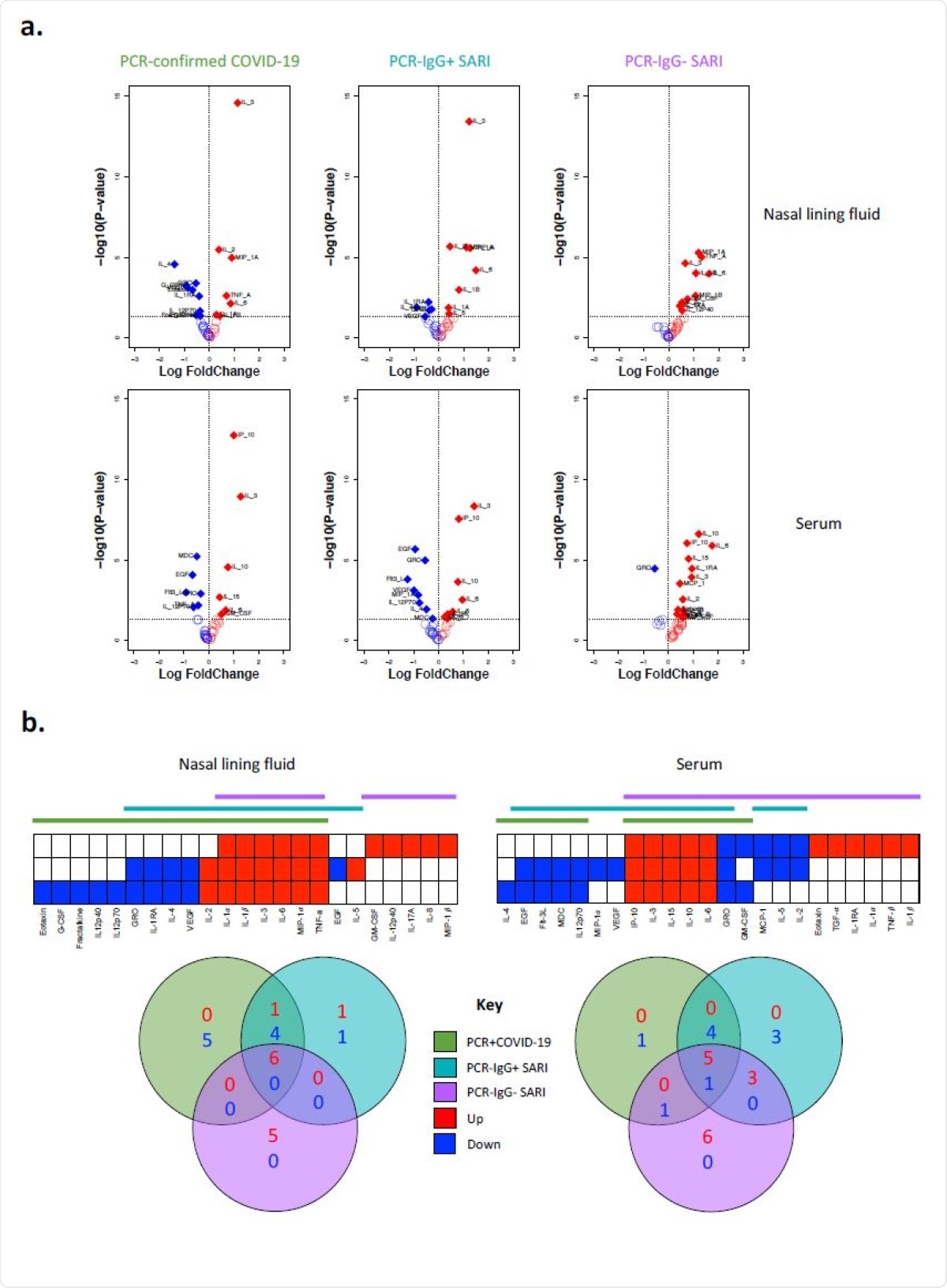

The team measured the concentration of 37 cytokines from the nasal lining fluid and serum samples of 25 patients with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2, 16 patients who were PCR negative IgG positive, 11 patients who were PCR negative IgG negative, and 25 healthy volunteers.

Compared to the healthy controls, results showed high concentrations of inflammation-related cytokines in the nasal lining fluid of all patient groups such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-1α, and TNF-α. The blood serum samples showed elevated IL-6, IL-10, IP-10, and IL-15 levels.

In addition, patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and patients with PCR negative but IgG positive showed a higher number of cytokines with lower concentrations in both the nasal lining fluid and blood serum than patients who were IgG negative.

There were also decreases in specific inflammatory cytokines. Low levels of IL-4, IL-1RA, GRO, and VEGF, but high levels of IL-2 in the nasal lining fluid were detected in patients positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The results demonstrate SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a distinct cytokine response in the nasal mucosa compared to systemic circulation. This also suggests that PCR-confirmed COVID-19 and PCR-/IgG+ SARI participants may be presenting at different stages of the SARS-CoV-2 infection spectrum,” wrote the researchers.

There were also greater amounts of neutrophils and lower frequency of CD3+ T cells in the nasal mucosa of patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and patients who were PCR negative IgG positive. Given similar immunological profiles in both groups, the authors suggest reclassification of COVID-19 status should be modified to incorporate IgG positive status as an indicator for infection.

Different bacterial and viral pathogens found alongside SARS-CoV-2

Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 showed low bacterial colonization. When the researchers tested for the presence of other pathogens in the nasopharyngeal/throat swabs of 80 patients, they found 74% had one or more of 12 respiratory pathogens on top of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. Excluding HIV, 14% of patients showed evidence of other viral pathogens.

About 27 patients had Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, this was after receiving ceftriaxone or amoxicillin within 24 hours of hospital admission. There were also low amounts of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae. The authors suggest this is likely due to increased use of beta-lactam antibiotics in the hospital.

In our study, severe COVID-19 patients exhibited distinctively low concentrations of VEGF in nasal lining fluid. Collectively, this suggests that the nasal mucosa could provide a snapshot of immunological activity in the lung in patients with COVID-19,” wrote the researchers.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Morton B, et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a distinct nasal cytokine profile. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.15.21251753, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.15.21251753v2

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News | Healthcare News

Tags: Amoxicillin, Antibiotic, Antibody, Blood, CD3, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Cytokine, Cytokines, Dexamethasone, Frequency, HIV, Hospital, Immune Response, Immunoglobulin, Inflammation, Neutrophils, Protein, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Spike Protein, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Syndrome, Throat, VEGF

Written by

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira

Jocelyn Solis-Moreira graduated with a Bachelor's in Integrative Neuroscience, where she then pursued graduate research looking at the long-term effects of adolescent binge drinking on the brain's neurochemistry in adulthood.

Source: Read Full Article