IT STARTED AROUND five years ago. My boys were two and four, my wife was a stranger, and my professional life felt like an avalanche of uncertainty and stress. In the morning, the air smelled like cinders; in the evening, the sun looked like blood. When people opened their mouths, I stared at them blankly. All I could hear was the howling of orcs.

More than half of guys who have symptoms of depression—and may benefit from antidepressants—don’t seek professional help. I’m not one of those guys. My primary-care doc handed out the candy: 150mg of bupropion, a starter dose. I whined, and she doubled it.

Life got less jagged. I discovered a newfound emotional resilience. Marital spats no longer led to bunkered isolation. A wind chime replaced the tolling of doom.

WLADIMIR BULGARGetty Images

These days, life feels almost Brady Bunch normal. Every morning, I wake up humming like an idiot. Feed the kids, water the plants, pop the pill. Heck, I could do this forever. Many people do. According to the CDC, 8.6 percent of guys 12 and older in the United States currently take antidepressants—up from 5.1 percent in 2002—and roughly one fifth of them have been doing so for ten years or more.

Thing is, there’s a lot we don’t know about antidepressants and how and why they interact with the brain, largely because we don’t understand most of the hows and whys of the brain itself. What we do know is that there is recent research that suggests that some antidepressants—including the class known as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)—may increase the risk of heart attacks, seizures, and dementia, among other things. Granted, the data remains pretty squishy—more correlation than causation. And no one has conducted long-term research on antidepressants for anywhere close to the amount of time people have been on them—in some cases 25 years.

But it’s enough to make you wonder whether the subscription model of mental health—$20 a month or whatever for a Tier 1 membership in the Sane and Functional Club—is all it’s cracked up to be.

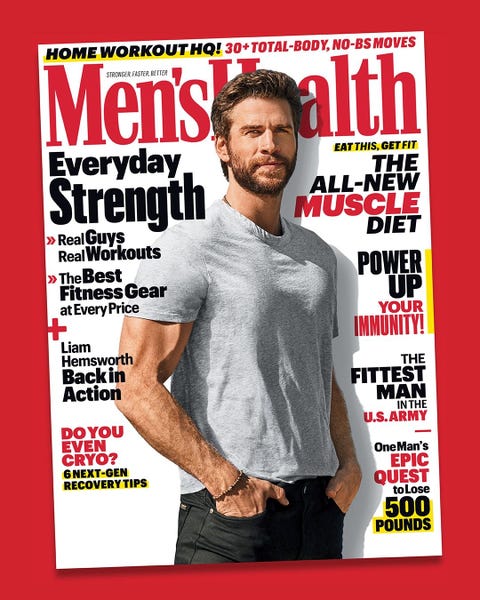

Subscribe to Men’s Health

hearstmags.com

SHOP NOW

It’s a tough call to make, particularly now, when the stigma of depression has finally begun to fade and we’re starting to take care of our heads the same way we take care of our bodies. Depression still carries liabilities that are at least as dire as the meds used to treat it—substance abuse, cognitive impairment, increased risk of heart disease, a more than 20 times greater risk of suicide—and much better substantiated. And discontinuing antidepressants entails risks of its own: relapse, primarily. Then there are all the potential withdrawal symptoms— fatigue, headaches, achiness, sweating, insomnia, nausea, vertigo, anxiety, irritability—which can sometimes go on for months or even years.

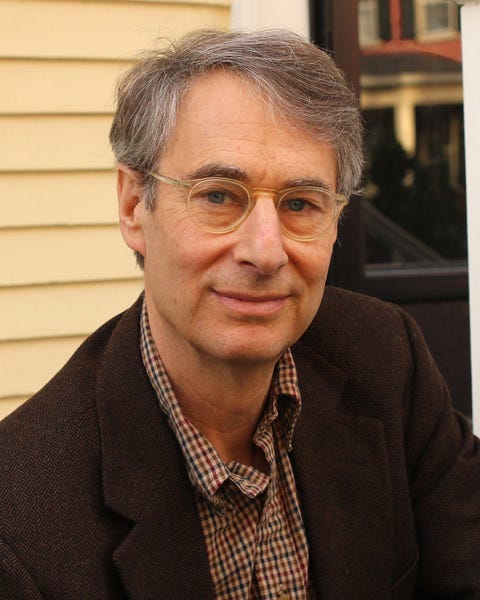

According to Peter Kramer, M.D., the éminence grise of modern psychiatry and author of Listening to Prozac (among a half dozen other books), people considering going off their meds can always refer back to one guiding principle: “In general, it’s better to be off medicine if you don’t absolutely need to be on it.”

By way of justification, Dr. Kramer cites something an old mentor once told him during his child-psychiatry training: “I never had to go back to a mother and say, ‘Remember that med we had your child on? They did some studies, and it turns out it makes children smarter!’ ”

On the contrary. If anything, the news always seems to be bad. (Remember Fen- Phen? Vioxx? Darvon?) This doesn’t mean everyone should shed their meds like last year’s fashion and take a purity pledge. There’s a calculus to be considered. “The main thing is you want to see someone doing really well for nine months, with no hint of any recurrence,” Dr. Kramer says.

And—to be crystal clear—this is assuming there’s no history of suicidality, hospitalizations, or multiple prolonged episodes, because there’s a difference between a single bout of mild depression and the recurrent, more severe variety. The latter you do not mess with. But even if your depression isn’t acute, it still makes sense to give the meds at least a year to do their thing. “Medications work by changing the brain,” says Drew Ramsey, M.D., an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, “and the brain is complicated.”

It may take months for you to understand how your medication has altered your brain. “Depression puts your life in a pattern that takes focus and intention to undo,” Dr. Ramsey says. “It’s not like, Oh, wow, my symptoms are gone, great. You have to repair things with people, and you have to repair things with yourself.”

Timing is another factor. Like maybe your dog just died, or you just got divorced, or you’re due for a romantic getaway— probably not the best time to wean yourself off the medication. Even the season can affect the decision. Winter can be pretty rough, after all. Why not wait for the birds to return?

There are also your dependents to consider. If you don’t have any, the decision is a lot simpler—if things go badly, the only one who suffers is you.

My two kids are older now, and the going is easier. The wife and I are getting on fine, and I’ve been doing pretty well for at least a year.

So, okay, now what?

It’s tempting to go cold turkey. Then at least I could turn my back with a show of bravado and recoup some self-esteem.

But no.

“Halve the dose for a week and see how you do,” my primary-care doc says.

I like my primary-care doc. She’s empathetic. She works hard. And she’s a primary-care doc, God bless ’er. She’s not in it for the money.

Yet even she’s wrong on this one. “We taper really slowly now,” Dr. Ramsey says. “Much more slowly than we used to.”

Jose Luis Pelaez IncGetty Images

According to a recent Lancet study, in fact, you should ideally be on the off-ramp for months. (To be fair to my primary-care doc, there’s no reason she would know this, given that even the American Psychiatric Association’s own guidelines still say “at least several weeks.”)

The Lancet study also suggests, incidentally, that your risk of withdrawal is vastly decreased if you lower your dose gently. Instead of a “Look, Ma” leap off a 300mg cliff, in other words, it’s gonna go better if you do it by halves—300 to 150, 150 to 75, and so on.

It all depends on the details, of course—the drug you’re on, how long you’ve been on it, and the size of the dose. Which is why it’s really important to talk it through with a doctor.

“I try to anticipate the side effects you’re going to have and then try to anticipate what the options are,” Dr. Ramsey says. “I want to hear about your mental-health game plan. Are you eating well, are you exercising, are you getting lots of omega-3’s and zinc and vitamin E?”

He may even go full herbal and prescribe Saint-John’s-wort—just as effective at treating depression as SSRIs, studies suggest. Even the herbals can have side effects, though, and interact with other medications—yet another reason to resist the urge to wing it. Consider this the first test in returning to a nonmedicated life. If you can do this right, then maybe you truly are ready to go it alone.

I am. I think. It’s been only two weeks, so it’s kind of hard to say.

Something else Dr. Ramsey said: “There’s a two-month period where no matter what happens, you wonder if it was because you stopped your meds.”

I can live with the lack of clarity, because even though the meds are gone, they left behind something important: a better sense of what works in life. A clearer picture of what that looks like. This was the gift. Now I just need to hold on to it.

Source: Read Full Article