When obesity occurs, a person’s own fat cells can set off a complex inflammatory chain reaction that can further disrupt metabolism and weaken immune response—potentially placing people at higher risk of poor outcomes from a variety of diseases and infections, including COVID-19.

A study laying out the details of this newly revealed cellular process was led by scientists at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and was published online June 2, 2020, in Nature Communications.

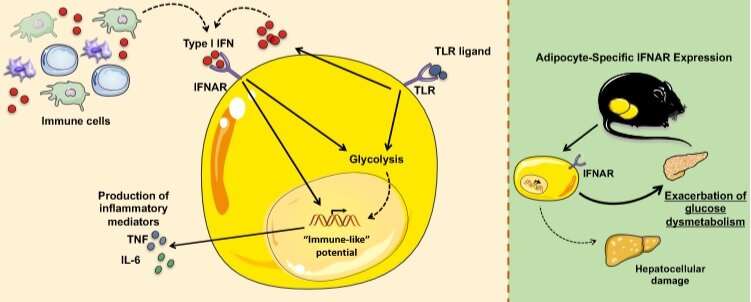

The team reports that type I interferons, a class of substances produced by immune cells also are produced by fat cells called adipocytes. These interferons drive a constant low-level, chronic immune response that amplifies “vigor” to a cycle of inflammation within white adipose tissue (WAT). More commonly known as white fat, this is the type of fat that expands to form most of the unwanted bulges around our thighs, arms and bellies.

This inflammation, in turn, appears to drive a cascade of cellular responses that promotes obesity-related disease, especially type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

“Our novel study reveals how Type I Interferon sensing by adipocytes uncovers their dormant inflammatory potential and exacerbates obesity-associated metabolic derangements. Further, our findings highlight a previously underappreciated role for adipocytes as a contributor to the overall inflammation in obesity,” says Senad Divanovic, Ph.D., corresponding author and a researcher in the Division of Immunobiology at Cincinnati Children’s.

Health risks of obesity include poor infection outcomes

Obesity affects more than 600 million people worldwide—and the US has the highest average adult body mass index (BMI) of all high-income countries. By 2030, roughly half of the U.S. population could become obese.

Long known as a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, cardiovascular disease, and diverse cancers, obesity also has been linked with elevated susceptibility and risk of developing serious complications to infection.

Obesity also was an independent risk factor for severity and mortality in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and is a risk for hospital admission and poor outcomes among those infected in the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Many studies have shown that obesity is much more complicated than simply eating too much or not getting enough exercise. Previous work has shown that obesity also reflects the outcome of various disruptions to how the body converts food into energy for our cells.

However, only recently have scientists begun to suspect that these excess calories could reshape fat cell behavior to affect the immune system.

Adipocytes revealed as new target for type 1 interferons

The new study shows how type 1 interferons operate along an axis of interaction with IFNa receptors (IFNAR) to trigger a vicious cycle of inflammation. Among the effects: changes in expression of several genes associated with inflammation, glycolysis and fatty acid production.

For example, mice fed an obesity-inducing diet displayed an augmented type I IFN signature including increases in Ifnb1, Ifnar1, Oas1a, and Isg15 gene expression, the team reported.

Importantly, many of the metabolic changes documented in mice were found to be conserved in human adipocytes.

This activity was unexpected, because until now most scientists have studied type 1 interferons in relation to viral infections and immune cell function.

“Our observations suggest that the type I Interferon axis can alter adipocyte core inflammatory programming to converge them closer to that of an inflammatory immune cell. Additionally, type I Interferons modify the metabolic circuit of adipocytes, which to our knowledge is the first depiction of immune-mediated modulation of adipocyte core metabolism,” Divanovic says.

What’s next?

Further investigation continues into the specific mechanisms that type I Interferons employ to modify adipocyte core metabolism. In addition, researchers continue to study the full extent of how adipocytes can “mimic” inflammatory immune cell capabilities.

“These findings directly impact an extensive number of patients, both adult and pediatric,” Divanovic says.

Source: Read Full Article