They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Now, researchers from Japan have found that even a mental picture can communicate volumes.

In a study published this month in Communications Biology, researchers from Osaka University have revealed that the meaning of what a person is imagining can be determined from their brain wave pattern, even if the image differs from what the person is looking at.

When we see images in real life, whether we are talking to a friend, watching a movie, or watching a beautiful sunset, our brains take in this visual information in a way that can be detected by a technique called electrocorticogram, which detects patterns of electrical activity in the brain. These patterns are not set in stone, however; they can be changed by what we are paying attention to or imagining at the time.

“Attention is known to modulate neural representations of perceived images,” says lead author of the study Ryohei Fukuma. “However, we didn’t know whether imagining a different image could also change these representations.”

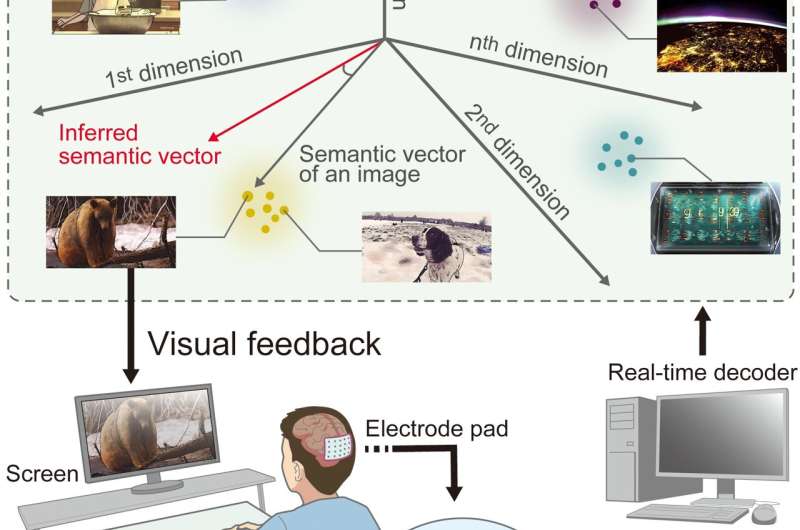

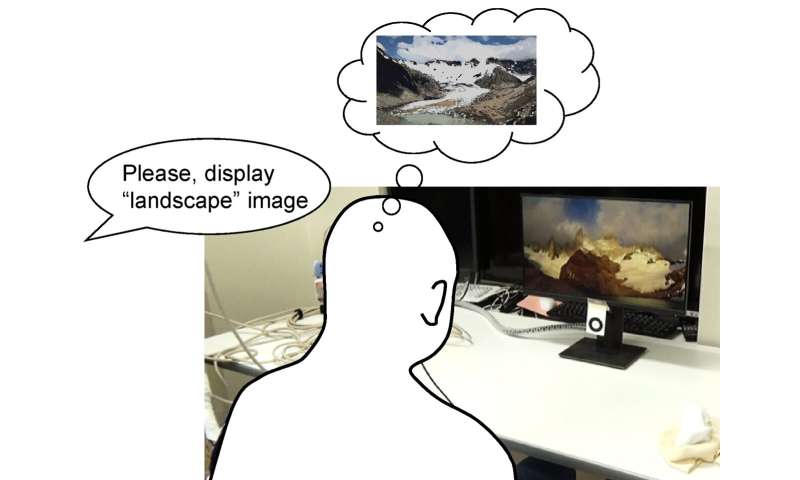

To test this, the researchers developed a new technology by working with patients with epilepsy who already had electrodes implanted in their brains to record and display electrocorticogram readouts of images that they were imagining. The patients were shown an image of the real-time readout and instructed to mentally picture a different image representing a “landscape,” “human face,” or “word” (for example, thinking of a human face while looking at various types of images) to control the readout.

“The results clarified the relationship between brain activities when people look at images versus when they imagine them,” explains Takufumi Yanagisawa, senior author. “The electrocorticogram readouts of the imagined images were distinct from those provoked by the actual images viewed by the patients. They could also be modified to be even more distinct when the patients received real-time feedback.”

The time needed to generate a very clear distinction between the imagined image and the viewed image was different for imagining a “word” and a “landscape,” which could have something to do with the different parts of the brain involved in imagining these two concepts.

“Our findings suggest that a readout image controlled by the subject’s imagery can be inferred by an observer using this technology,” says Fukuma.

Source: Read Full Article