A protein newly identified as important in type 1 diabetes can delay onset of the disease in diabetic mice, providing a new target for prevention and treatment in people, according to research led by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Indiana University School of Medicine. Because type 1 diabetes is incurable and has serious lifelong health consequences, prevention is a major research goal.

The key to the new study, published online January 9, 2020, in the journal Cell Metabolism, is a technique called mass spectrometry, which can comprehensively detect proteins that are found at extremely low levels in the body, but can have large effects on health.

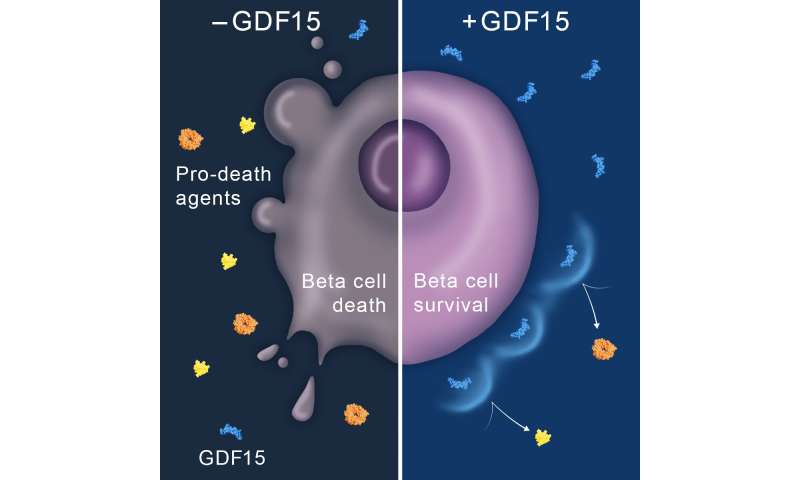

The multidisciplinary research team of physicians and biochemists used a new strategy to pinpoint proteins in beta cells, a subset of pancreatic islets that increase or decrease in response to immune system attack. Beta cells normally regulate blood sugar levels in the pancreas. In people susceptible to type 1 diabetes (previously called insulin-dependent or juvenile diabetes) these cells are slowly destroyed by the body’s own immune system. Here, the researchers focused on how islets respond to inflammation.

The researchers treated human pancreatic islets with substances produced by the body and thought to be involved in the diabetes disease process. They identified a total of 11,324 proteins, with 387 affected by the treatment. Of these 387, they narrowed their focus to one: growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15).

“We wanted to identify proteins that can intervene in the diabetes disease process,” said Ernesto Nakayasu, a biomedical scientist at PNNL and co-lead author of the study. “We became interested in GDF15 because the protein level was suppressed by 70 percent after treatment.”

GDF15 is known for its protective effects in different types of cells in the human body but it had never been studied in islets. When the researchers measured levels of GDF15 in pancreas tissue from people with diabetes, they found the protein was depleted in their malfunctioning islet cells.

But the key piece of evidence emerged when the scientists treated non-obese diabetic mice with GDF15, and it reduced development of diabetes by 53%. Non-obese diabetic mice are a common model for testing type 1 diabetes treatments because they spontaneously develop autoimmune diabetes with many similarities to the human disease.

“We hypothesized that reduced GDF15 was not a good thing for islet survival, and indeed that was the case,” said Raghu Mirmira, a study principal investigator. “This work opens the way for us to consider these sorts of ‘islet protective factors’ as therapies to prevent or reverse type 1 diabetes.” Mirmira until recently served as professor of pediatric diabetes and director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Indiana University School of Medicine. He is now a professor of medicine in the Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism at the University of Chicago.

“This approach differs substantially from current thinking that targets the immune system. While GDF15 may be one new therapy, we identified other proteins that may work in conjunction with GDF15, so this work really represents a treasure-trove of information that can be mined for new therapies,” said Mirmira.

PNNL’s Tom Metz, the co-principal investigator and an expert in mass spectrometry-based proteomics of islets, agreed, adding, “This study illustrates the power of non-reductionist, comprehensive approaches, such as proteomics, for discovering new information in complex systems. The protective role of GDF15 against islet destruction and its ability to delay onset of type 1 diabetes in the mouse model would have been very difficult to discover without performing the initial comprehensive proteomics analysis of stressed human islets.”

The researchers are now working on the idea that low levels of GDF15 in islets may somehow be playing a proactive role in instigating the autoimmune attack that ultimately kills them.

Source: Read Full Article